“Bread-interview” with Giulia

Maciej: What is your relationship with bread?

Giulia: Pretty good, (smiles). My relationship with bread started about a year ago, out of interest and curiosity. I didn’t have much knowledge about bread, before that.

I felt drawn towards it. While researching different food and food cultures, I have realized that bread is kind of the base of all of them and the base of our nourishment, so I wanted to look into it more.

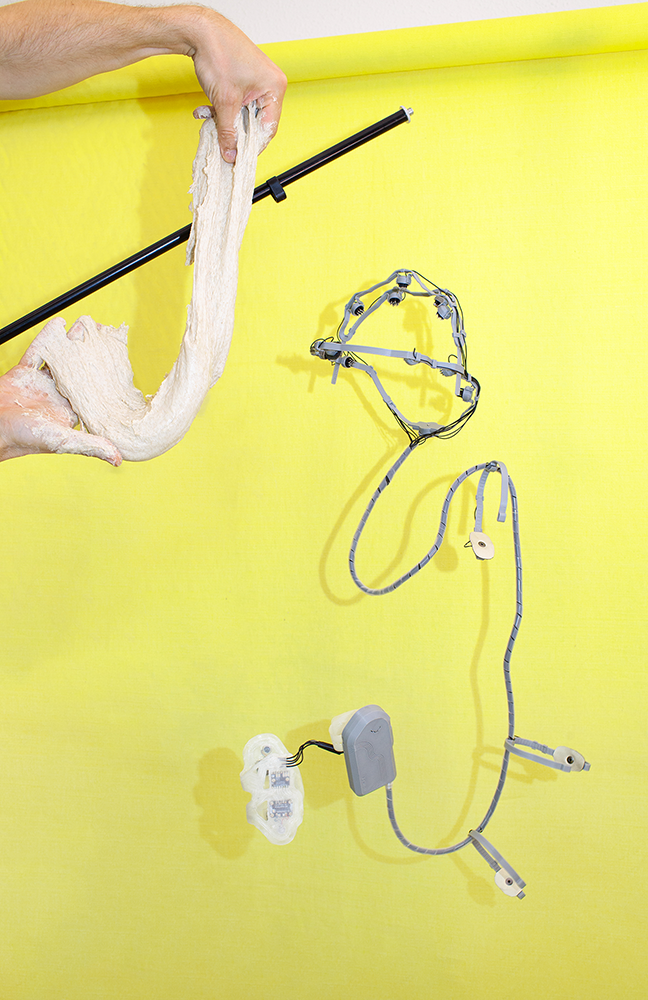

I started to work in a sourdough bakery, learning how to follow the process and getting my hands dirty. I learned to understand what it means to produce bread and to be part of the act of producing bread, to give bread to other people and thus to feed other people, to nourish people.

M: You told me that at the beginning you were a bit annoyed by the dough.

G: I got annoyed by the stickiness at the beginning. In the bakery where I am working the hydration is very high, so it’s always very sticky. But at one point it just doesn’t stick anymore or one gets used to it and learns how to handle it.

M: When I was learning to make pizza, I believe that my hydration wasn’t high enough at the beginning and I learned my way through to a higher hydration. But when I tell people today how to work with a pizza or bread dough, I see how difficult it is to explain how to position your hand and what movement to make. The result is very often, especially with my children, for whom it seems fun, that dough is everywhere, and their hands and the bowl are connected with these sticky dough strings and everything is super hard to clean. But when you hold your hands in a certain position and work with a certain speed and a good flow, even highly hydrated dough acquires a dynamic of its own and doesn’t seem to stick at all.

G: I think, anything you do – I mean I don’t like the word train, but at some point your body knows how to act, how to move. At one point there is kind of a switch. But yes, without experiencing it it’s very difficult to explain.

M: Can you tell me something of controlling or perhaps losing control of the dough?

G: I have a greater fear of losing control with pastry than I have with bread. Because with pastry, you follow a recipe very exactly, and then it’s uncooked and you just put it in the oven and wait, you cannot adjust anything. Perhaps I had it a little with bread in the beginning, but now it’s different, I also taste the raw dough while making it. This morning I probably ate 200g of raw dough, and tasted the starter. You can also see if it’s fully developed, or check the texture, or stretch it. Actually, you can control a lot in the process of bread making.

M: What you are describing already requires a higher level of experience. From the very many breads you have baked you know what the starter or the dough should taste like to get to a good result. But the taste of the raw dough, even the saltiness of it, doesn’t have so much in common with the taste of the finished baked bread.

G: Yes, that’s true and perhaps it’s also just ok at a certain point. When you form the bread, put it in the fridge, it’s an act of fate or trust that the process will go well and you leave the control to the bacteria that continue your work.

It’s always like this with fermentation, you can kind of guide it, but actually not control it anymore.

M: How did you get into cooking and working with food?

G: I got into cooking thanks to my dad. My mum is not that kind of traditional Italian mum. When we were on holiday or traveling, he was also the one who was more curious to discover local ingredients, going to markets and then opening the bags and finding out what we could cook with it. It became a nice activity that me and my sister shared with him. Spending time together preparing and then eating together.

Starting my research, I got into cooking even more. I started to feed other people to better explain my projects and also test these on them. I started from what I knew, worked with raw ingredients, and much simplicity, how to transform them without changing too much of their nature. I like people to recognize what they eat.

And later I learned very much about cuisine from other people I worked with.

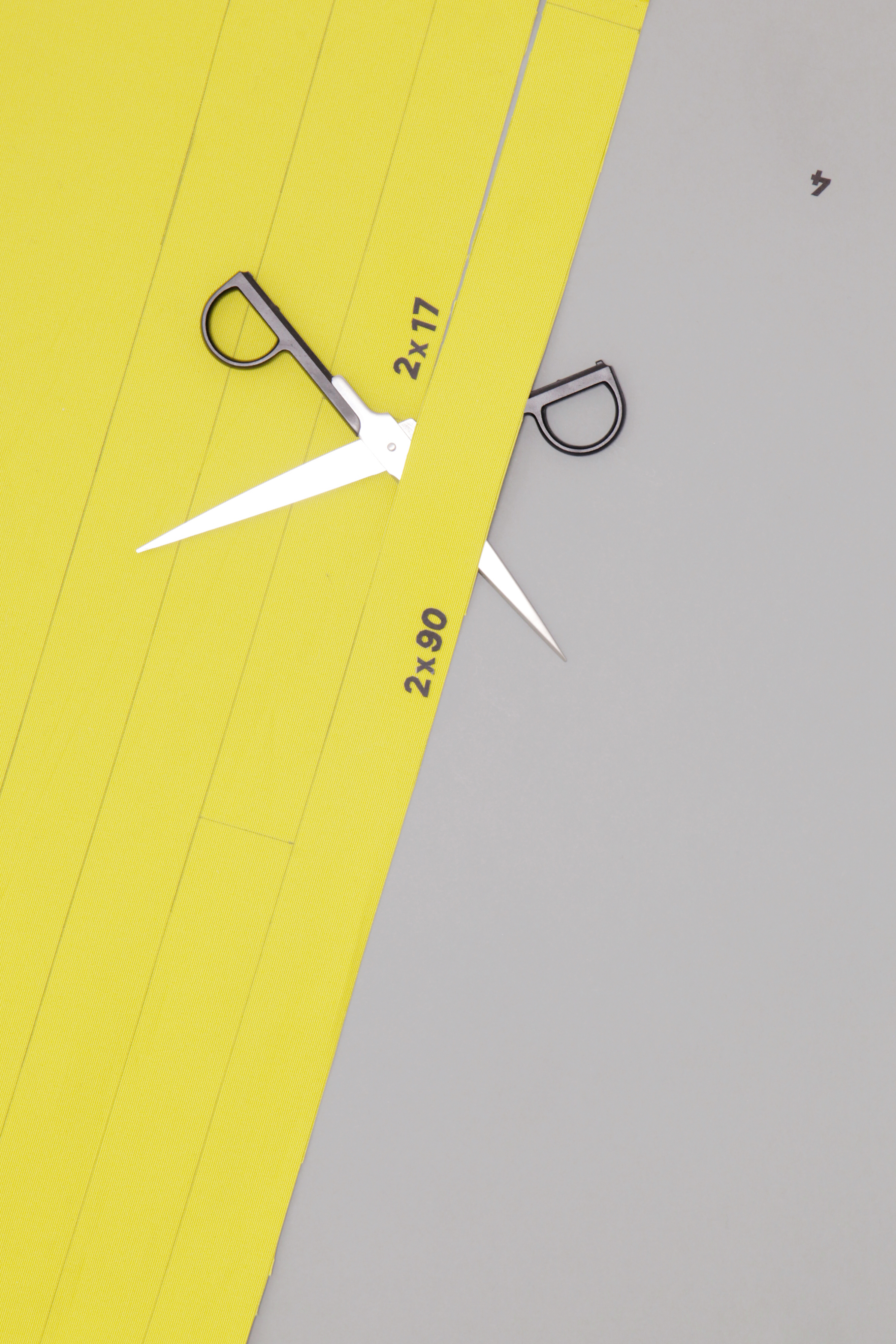

M: You talk a lot about the sensuality of eating, and of cooking. About learning to cook by observing hands and movements and that cooking is the interplay between your senses and the ingredients. Looking at it from this point of view, how would a good bread recipe look like – or is it even possible to write one?

G: I think yes, it is possible. I thought a lot about how you can interact with your body while cooking and how to understand this. Perhaps it’s not a perfect recipe at the beginning, but one that you have to repeat more often, so your body acquires the knowledge. Maybe it would be a visual recipe, where you can follow the gestures of the hands. And by this to learn that your hands are the tools and not to start with a machine from the beginning. You can gain awareness of what you are making.

M: Last time we were also discussing other ideas of how to communicate intuition or improvisation in cooking, or how you can use your hands as a measure, and we came to the conclusion that perhaps a hyper-precise recipe in the form of a text that you first have to study very exactly, might make sense.

G: …maybe yes. In my projects I call these series of movements choreography of hands. In order to be a choreography, they have to have a script. So maybe yes, maybe we need hyper-precise scripts.

M: The description as a choreography is very interesting. In dance there are different commands that represent a series of movements, it is a language that the dancer has to learn to be able to understand and perform.

In our case, the text would need to explain individual movements and series of combined movements that we have to learn to later follow the commands of the recipe.

G: Actually, I tried to do something like this in my projects at the beginning. I created a vocabulary for it. The definition of a movement was defined by a series of actions.

M: The olfactory sense has an extremely direct connection to our memories and our emotional centre in the brain. Freshly baked bread, with its complex and beautiful smell, releases memories, situations or culinary emotions in most people. What is your personal bread moment?

G: There is a special bread smell that I recognize more in Italian bakeries than in others. It’s kind of a Ciabatta smell, not really sourdough. We had a bakery next door, and I have a strong memory of standing in line, queuing with my dad and waiting to get a bread on Saturday morning. And when you got it, it was still warm and you could try to steal a piece or perhaps someone gave it to you.

But there is also another one. It’s a bread with caraway seeds that I ate when I was on holidays in the north of Italy with my parents as a kid.

I disliked it because I didn’t like the taste of those seeds.

It goes kind in the direction like anise and fennel, it just was too strong. In addition, it was a dark bread, probably rye flour. I recently came across it again, and wanted to replicate it, bake it at home and it took me back to my memories. It was a nice exercise to go back in time with the help of baking.

M: I have to say, that also one of my strongest negative bread memories is connected to bread with caraway seeds. When I started to study in Linz and I bought bread or rolls in a bakery, everything was with caraway seeds. And I was shocked when I ate this with strawberry jam, I didn’t understand why anyone would put this spice in their bread.

Today I also add caraway seeds, fennel, anise and other spices to the bread, especially on cold days to accompany a nice soup, but surely the amounts I use are still very subtle compared to Austrian breads.

M: Let’s talk about your bread project in Milan. You recently gave me a beautiful description that I still have in my mind. You said there was no discrimination of bread today. What did you have in mind with this?

G: The general idea of the project was to recreate a kind of landscape of different breads on the occasion of a meeting of the design academy Eindhoven in Milan. After starting to working there (Eindhoven) I was inspired by the international environment at the academy. You can meet people from every part of the world there.

I realized that we always meeti in this international context and that food always accompanies the gatherings. It supports discussions, that’s also why I started to work with food. I wanted to recreate this feeling of different cultures coming together and so I used bread from different cultures and basically nothing else. On the one hand you show the differences and the diversity, but on the other hand there is no real diversity, because in the end it’s just bread.

So in this sense there was no discrimination, all kinds of bread are breads.

I also told you about my experience in Apulia last year. I was at a masseria (a farm, the Masseria Cultura in Noci) and wanted to bake a bread from the countryside and recreate the specific shape and taste of the wood oven. And in the end I just couldn’t handle the heat of Apulia, it was like 40 degrees, my dough was exploding and I didn’t have any experience with wood fired ovens. In the end I just used the heat to bake flat breads on stones. I realized it’s just flatbread, but it’s still bread. Talking about bread we like to think of beautiful loaves, but every mix of flour and water that is baked becomes a bread.

M: Let me pick up on this. A few weeks ago, I was sitting in Oxford and discussing with a few people from different background what the definition of bread actually is. Do you have an answer to this question, what is a bread?

G: You know, since you have asked me this question the first time I have been thinking about it every single day. And I will definitely ask my colleagues at the bakery as I am curious what they will say. But me, personally, I would not consider for example a pain au chocolat bread, I would go for the essence. When you take grain and grind it and add water and if you like other elements, it can be salt or not, it can be yeast or not, it can be other additions or not… you bake it and if this nourishes you, that’s bread.

I think.

There should be a kind of transformation. Pain au chocolat or banana bread, maybe they are still part of the family, but they lose a bit of…

M: Purity?

G: Yes, but it is also something else. Bread comes from the necessity of feeding. And when you have a pain au chocolat, there already is the further aspect of pleasure there. I am not saying that this is bad, but when I think about the essence of bread, I think that it comes from a necessity.

M: Do you have a bread or a bread recipe that you absolutely favour, that would be the only bread that you could eat until the end of your life?

G: Right now it would certainly be a rye sourdough bread, but if I may give a more emotional answer, it would this Italian small bread that is very hollow inside and has a very nice crust.

M: I wouldn’t like to miss the contrast of simple breads, the softness and fluffiness crumb and the crunch of the crust.

G: That’s why I mentioned this Italian michetta. They are or have been quite traditional in Milan. Nowadays it’s not that easy to find them. They have this kind of turtle shell shape and are amazing for making sandwiches. The bread becomes a good partner with what you put inside, it doesn’t overrule it, but you have this amazing crunchiness that is on the outside, when it’s well made and on the inside you don’t have much of a crumb, it’s quite hollow. So as a bread it’s a pretty specific one and the smell of it and the crunch of it is really, really nice. But I am with you, that the contrast is important, I like a soft crumb as well.