Brot: Baking the future

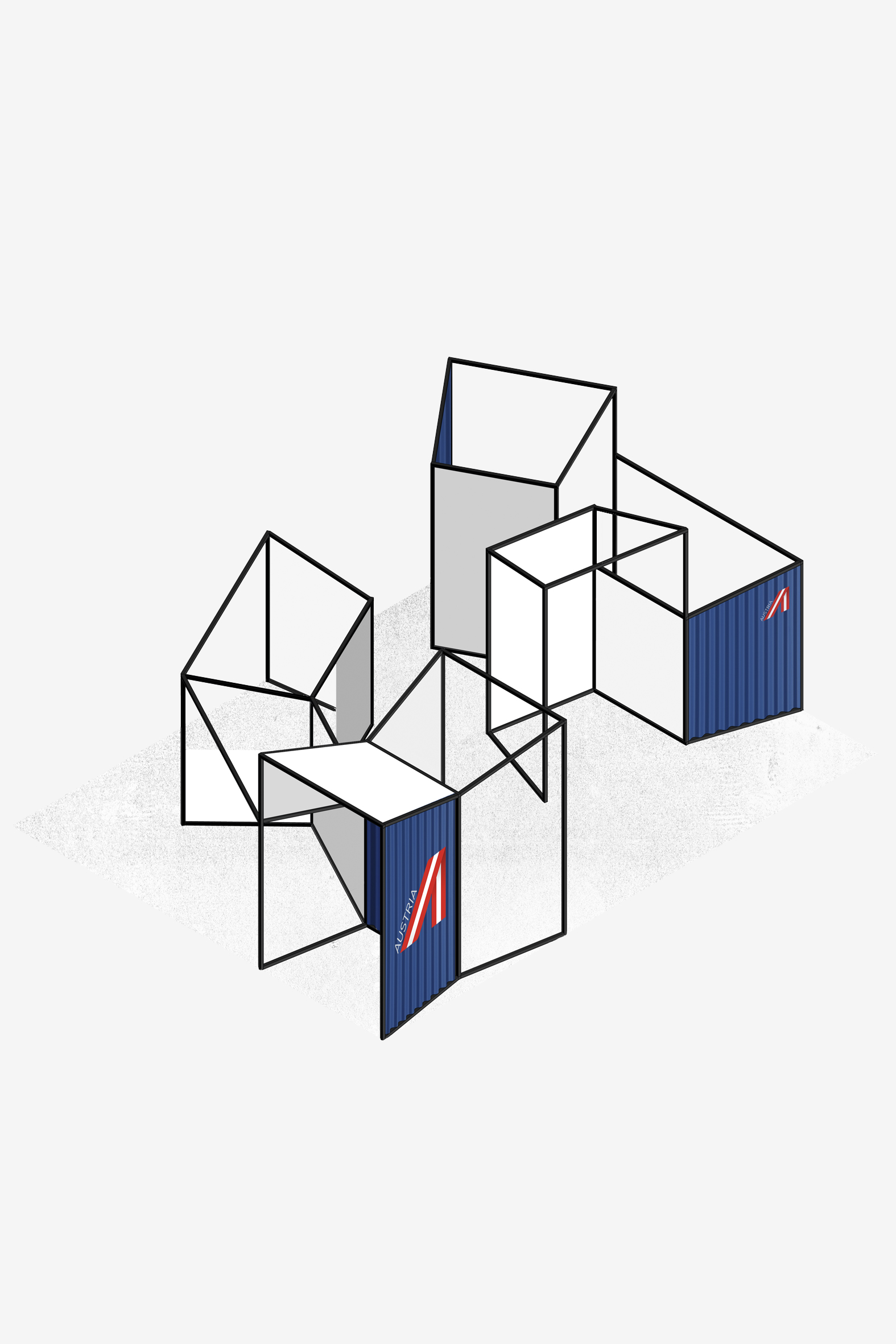

Austrian Pavilion at London Design Biennale

1-25 June 2023

A loaf or slice of bread may seem simple, but there is a curious complexity to the matter of bread. From geopolitical contexts to microbiological processes to multi- sensory experiences, bread and bread making can open up a whole new universe and pathway for transformative design practices. Together with the curator Thomas Geisler, the design duo Chmara.Rosinke addresses and explores the complexity of bread in this year’s Austrian pavilion at the London Design Biennale 2023.

Bread is eaten daily in Austria and many countries around the world. This staple food is often a main source of nutrition. In the Global North, bread is usually taken for granted and food scarcity is rarely addressed – its geopolitical implications, or the impact on the social stability of individual countries.

In recent years, there has been a cultural surge around bread. Bakeries that look like sleek boutiques are popping up in urban areas, and home bakers are handling the subject of sourdough with almost scientific meticulousness, sparking a private war against the heavily industrialised production of bread. The psychological stress of the global pandemic lockdowns has only intensified the incipient hype of bread baking.

What can we learn from this complex and fascinating subject area in relation to the discipline of design? Education about fermentation is one – it has cultural and historical origins in bread and beer. This process is more widespread in the medical technology and food industry than we may think. In the form of precision fermentation, mankind is making even greater use of the capabilities of microorganisms and will revolutionise food and material production in the coming years. But above all, bread as a product and its production is emotionally charged.

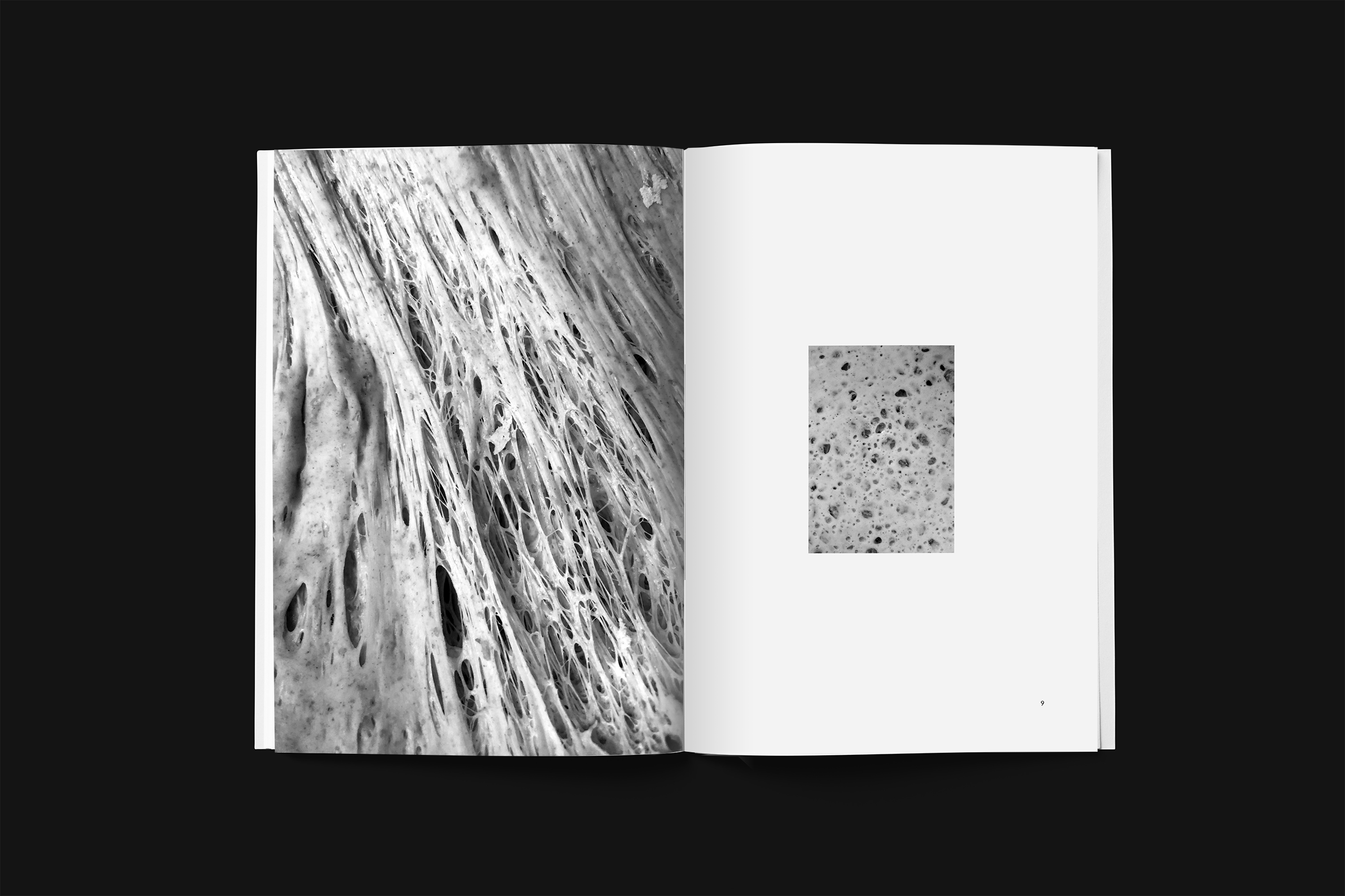

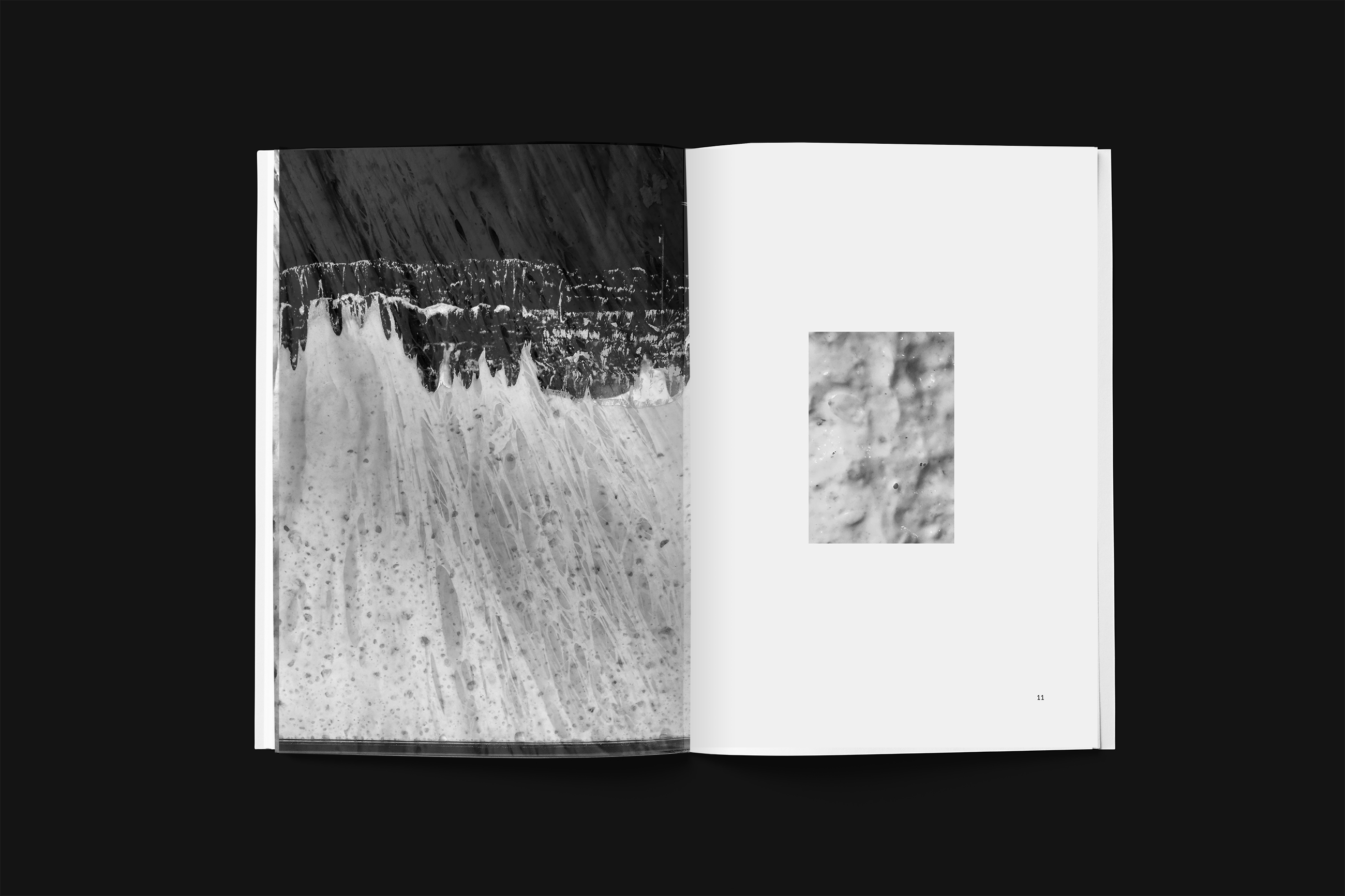

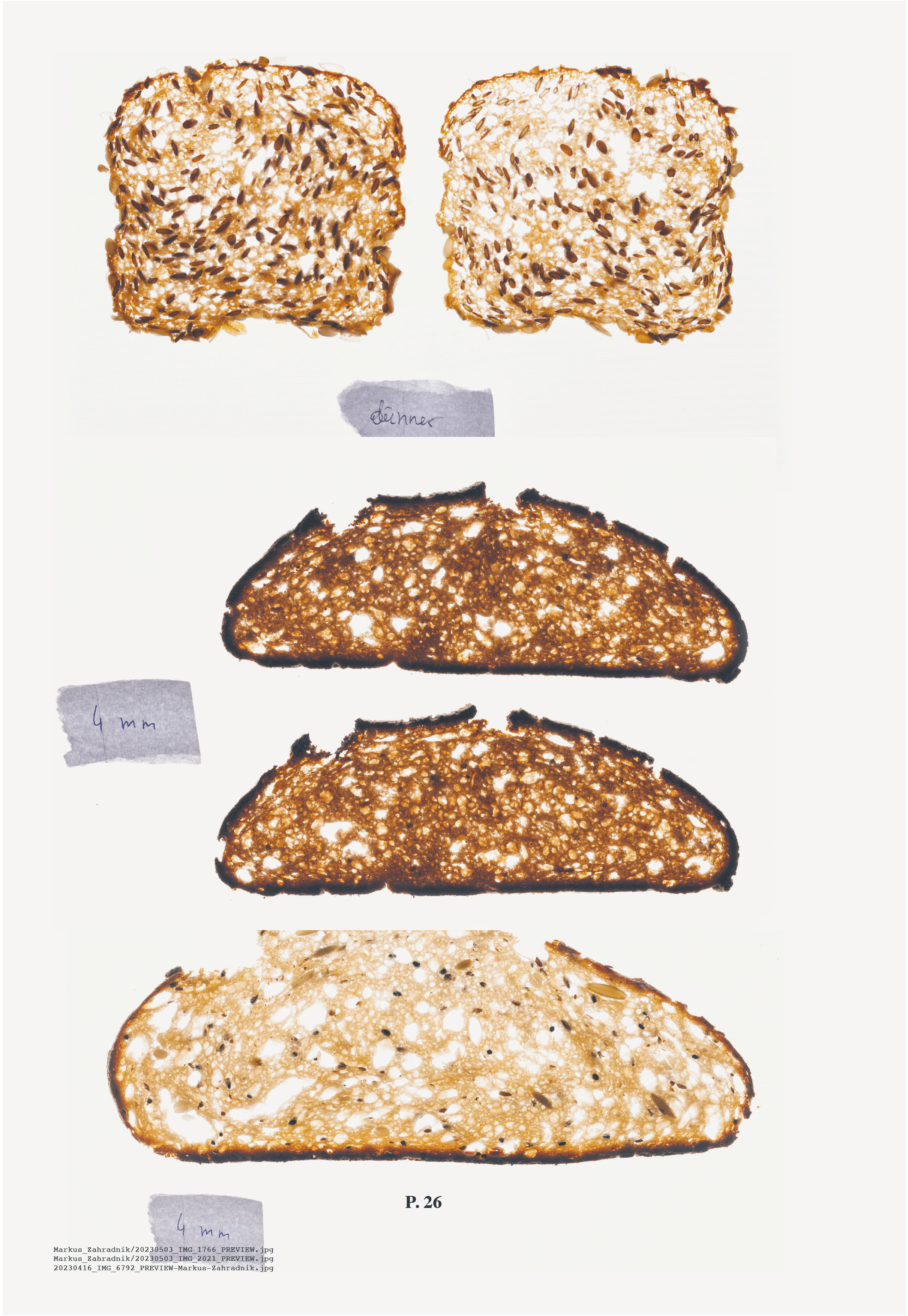

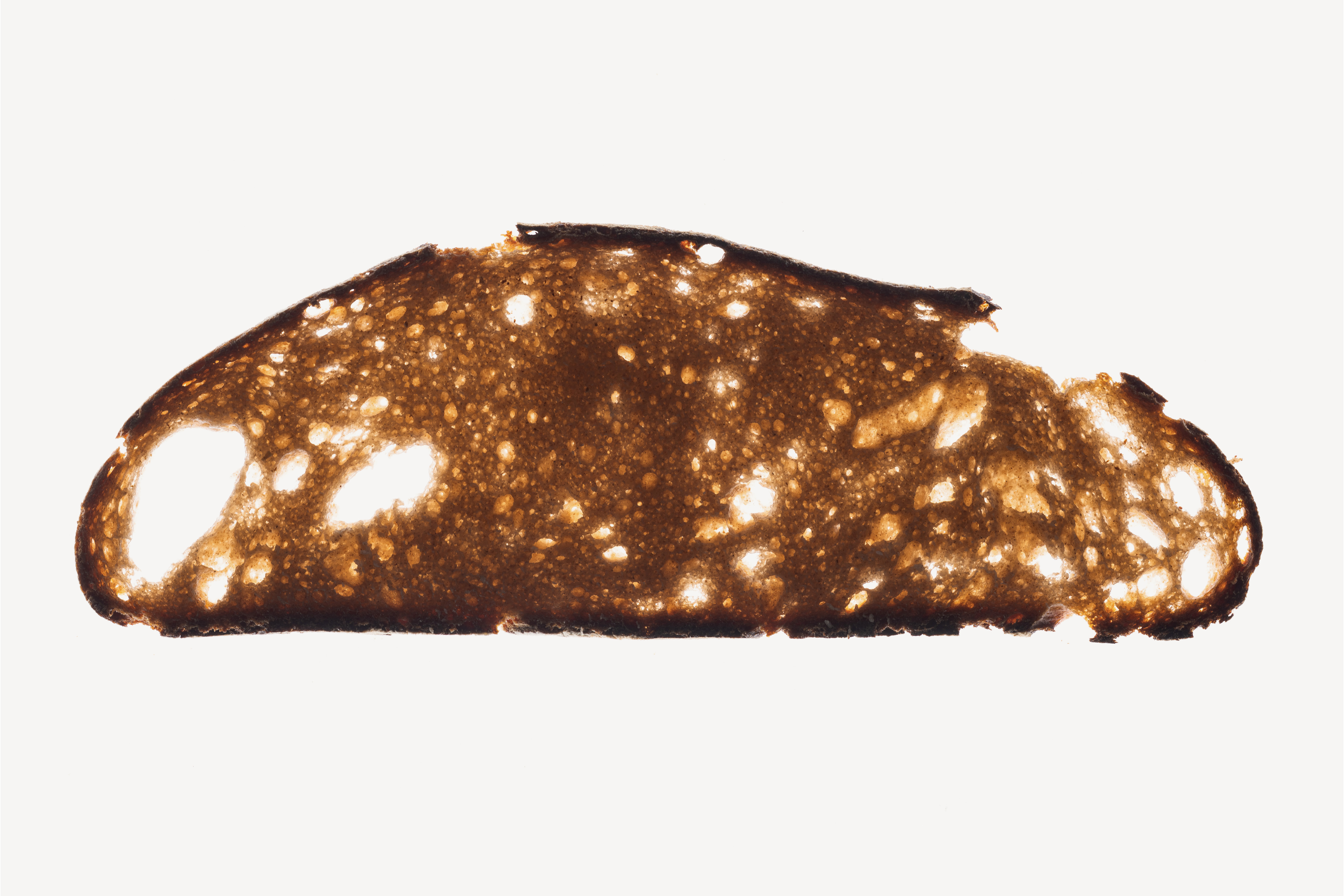

The focus of the Austria pavilion is on the sensory experience of bread. The colour, shape, tactile properties, smell, and taste of a freshly baked loaf are just as important as the sensuality of the process. Dough processing and bread baking are multi-sensory experiences that have therapeutic qualities and can achieve a whole new significance in our time as a cultural technique and source of inspiration in a transformative design practice.

Three speculative scenarios :

Our society, culture and therein specifically architecture is based on the fact that mankind has started to bake bread and brew beer. The three speculative scenarios we show in the exhibition "BROT: Baking the future" are by no means dystopian visions of the future, but rather alternative realities that put our own existence and the use of bread in a different light.

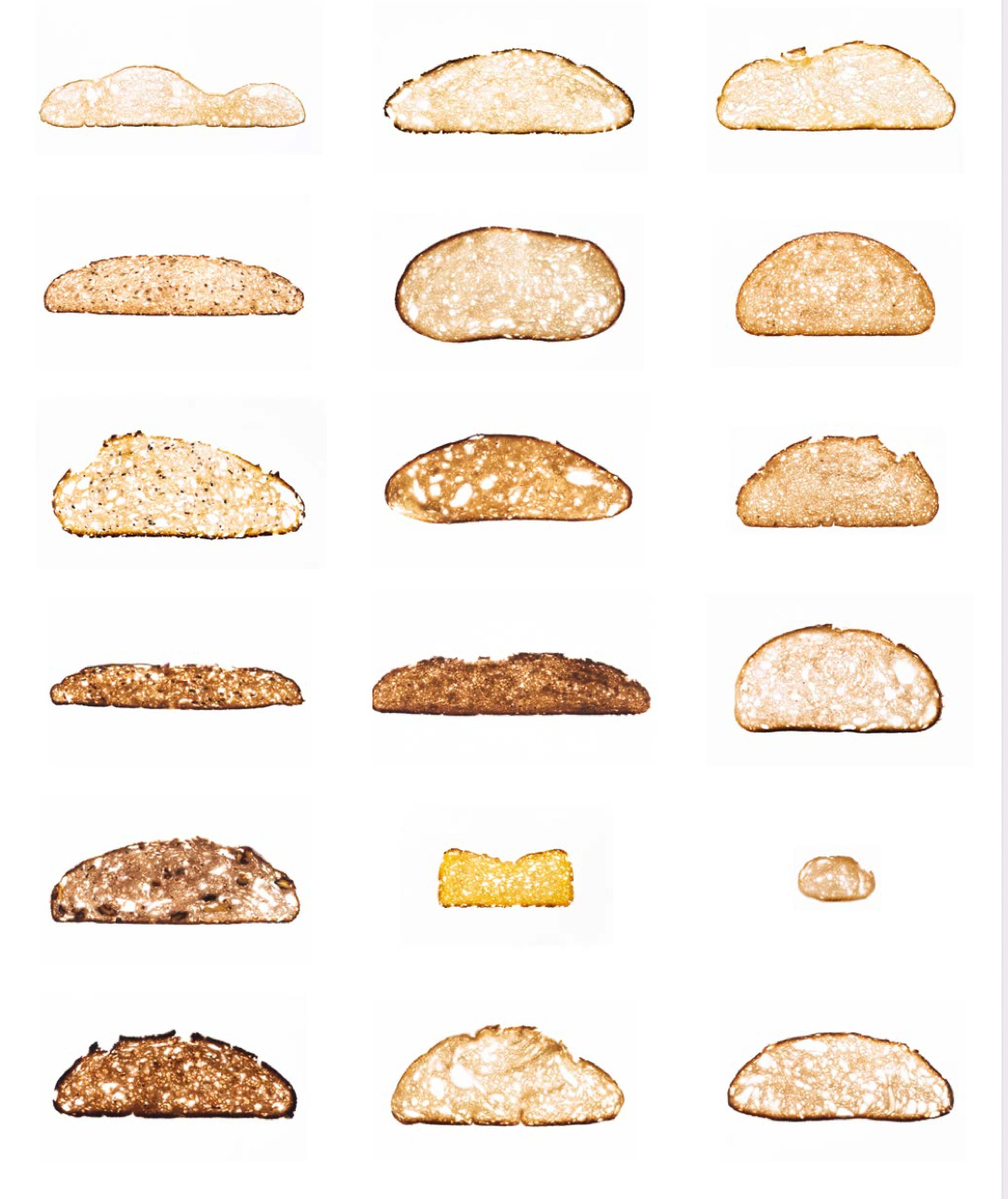

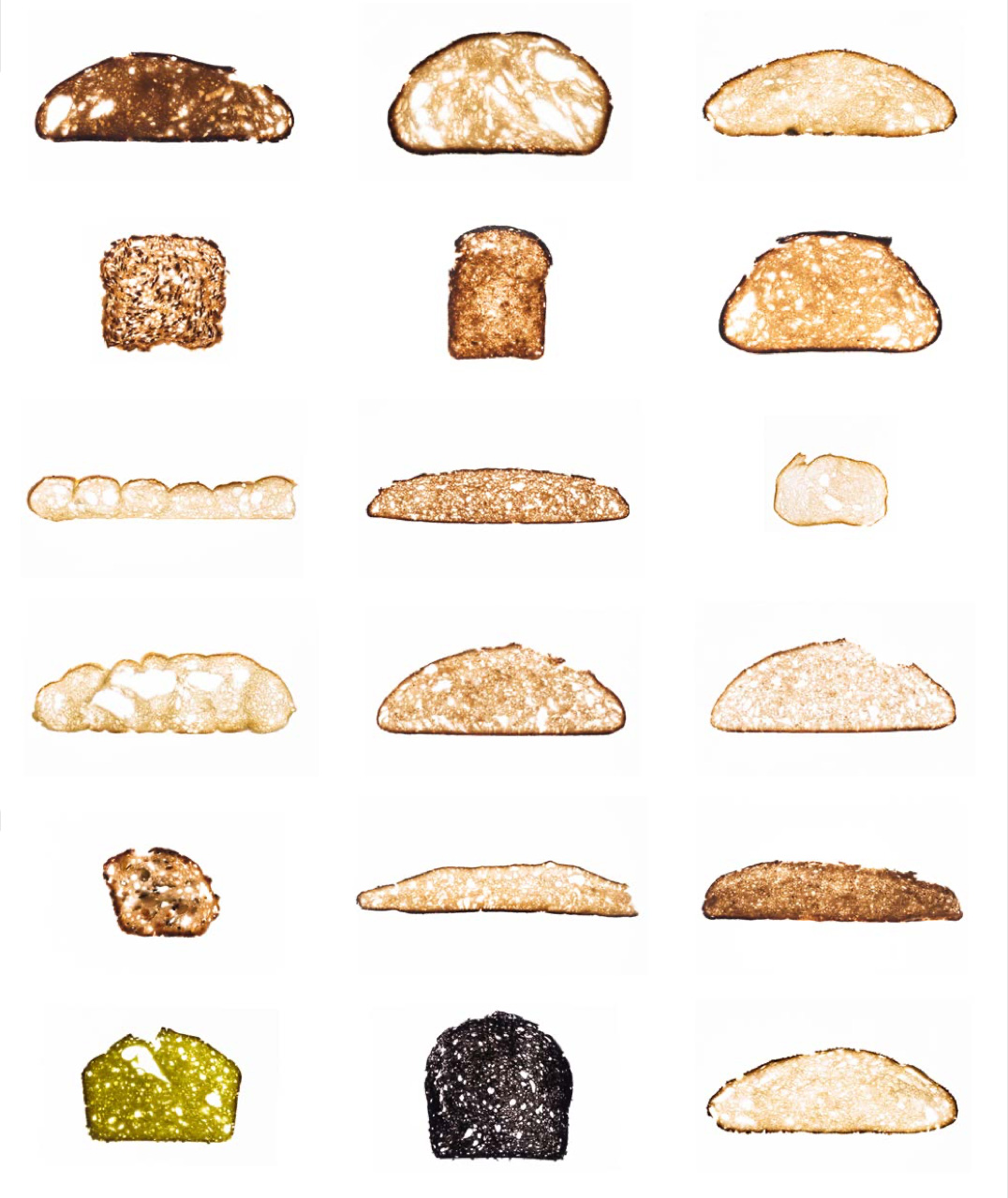

1. Bakers and Gatherers

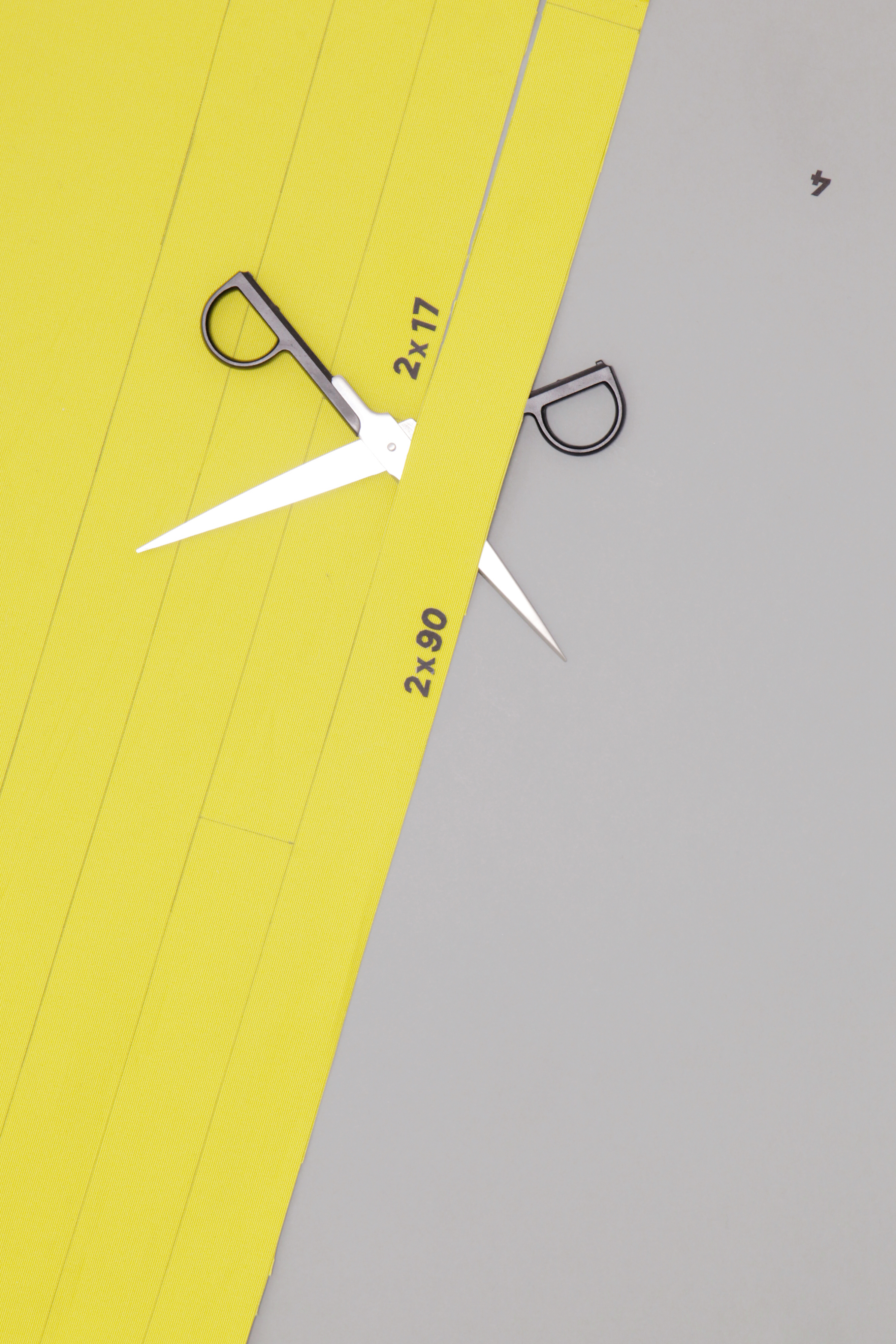

The "Bakers and Gatherers" are a technology-critical society who, in a world affected by climate change and pollution, see the only way to restore balance in the world, is in gathering the ingredients for their bread. They live in small societies of 10-15people, where each person plays an important role in the process of gathering as well as baking. They are also strict about not having too many children so as not to upset the balance. The breads are seasonal and are prepared with water harvested from birch trees and thus purified. Other ingredients are mealworms, which settle in the flour anyway, and other insects they find seasonally. The insects enrich the bread with proteins. Since the grain for the flour is also gathered wild, many alternative grains such as buckwheat have to be used in addition to classic cultivated grains such as wheat or spelt. The incorporation of seasonal wild herbs such as wild garlic or dandelion and the temperature differences in fermentation bring great seasonal differences to the breads. The bread is worked in a circle with a small cut. Exactly this shape corresponds to the shape of the baked breads. The bread is baked in a solar oven with stone storage, so that bread can also be produced on sun-free days. Electricity and other newer technologies are only used in exceptional cases in the form of solar cells and a specific multitool. This multi-tool serves as a helper in gathering, cutting, chopping, but it also includes a scanner to check the food for parasites, which have become a greaterthreat due to climate change. Electronic components are obtained through bartering with the Cyber Yeast Society and the Brotonists.

2. Brotonists

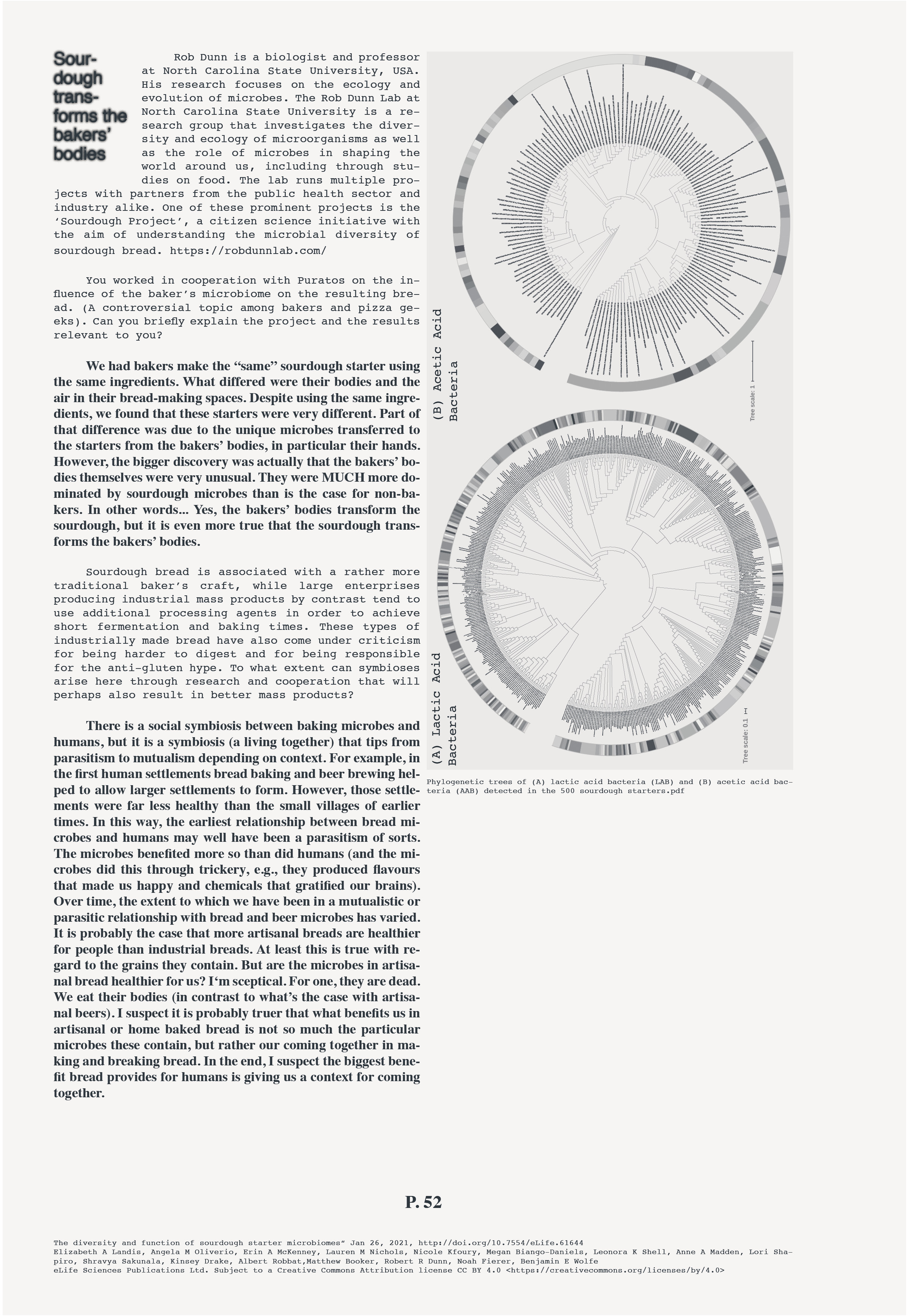

The "Brotonists" is a quiet, somewhat conservative baking society that has a cult-like reverence for bread and the process of baking. Once a week, everyone lines up in front of the main building where the ingredients rye, spelt, emmer, wheat, water and salt are distributed. Each person receives the same ingredients. Nevertheless, the society is strongly characterised by hierarchies. Due to the differences in the microbiome of the people baking, different breads are produced with the same ingredients. Even if this can be influenced by therapies, these people are less respected. Status symbols of this society are the oven and the sourdough shrine. A piece of furniture to precisely temper different sourdoughs and maintain the perfect humidity.

The reverence for the process of baking bread is evident in the beautifully crafted bread-making tools. Everything is crafted from silver fir, which has antibacterial properties, and hornbeam, which is also used to make gears for mills. The highest art form of this society is the scoring of the bread. Each loaf has its own pattern: cross, circle, curved line and the rye bread, of course, burst open. The art here lies in simplicity and perfection. Everyone is allowed to bake, but the ceremonial scoring is left to the head of the family. To relax, the members of this society listen to different bread crusts in their bread player or smell different mixtures of ingredients. The shape of the yeast is celebrated with vessels or ceremonial proofing baskets. Once a year, all bread doughs are put into the ceremonial "mother yeast" and fermented in it. The individual microorganisms and individual doughs partly mix in this process.

3. Cyber Yeast Society

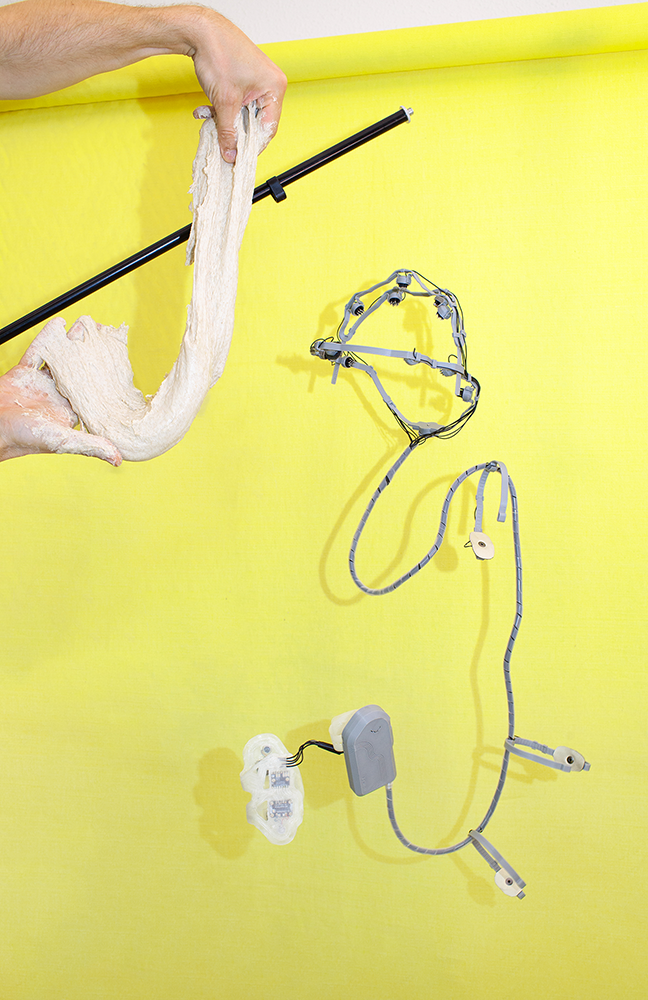

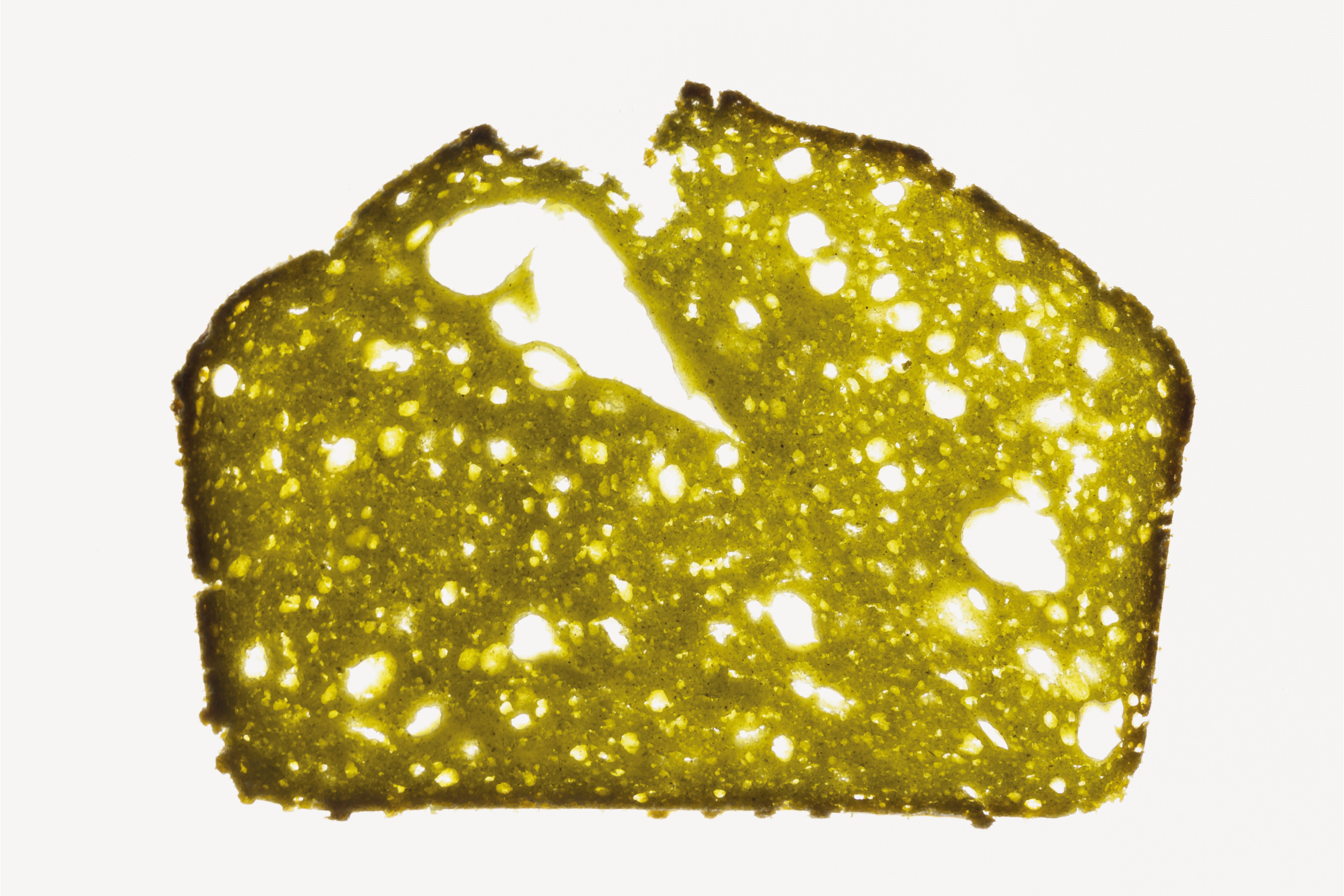

The "Cyber Yeast Society" is a society of hedonistic loners. However, they meet once a day as a group in the "dough and sweat centre". Here they do fitness, while they work on dough, in the sense of multisensory experience and strive for physical and mental perfection. The time they spend changing clothes after training, showering and performing the prescribed sexual intercourse is enough to ferment and bake the enzymatically modified dough. Through regular genetic sequencing of their microbiome, an individual supplementary sourdough is mixed, enriched with various necessary microorganisms. The yeasts used in the sourdough are genetically modified and able to ferment microplastics from the environment into proteins. The wheat is Crispr modified to achieve the ideal texture and crust-to-crumb ratio, but also to provide vitamins and nutrients that are otherwise lacking in this bread diet. Depending on their social status, individuals in the society receive better or worse drugs in their sourdough, or may also earn extra green breads in some cases. Their standard bread is black and rectangular. They carry it in a bread box strapped to straps around their upper body.

The installation is just the starting point of the materialization of a research project on bread and baking as a cultural and aesthetic practice.

We would like to grow our project over the next few years and create an interdisciplinary network that not only connects us through the fungi and microorganisms that live in symbiosis with us and help us make bread, but also provides potential for interdisciplinary work on the complex problems of our time in the context of ecologically responsible food security.

We'd very much like to thank all supporters and partners of this project.

Curator: Thomas Geisler

(Design Campus, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden)

Main sponsor:

Federal Ministry for Arts, Culture, Civil Service and Sport, Republic of Austria

Support/Cooperation:

Austrian Cultural Forum, London

German Design Council

Goethe Institute, London

Design Campus, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Oxford - UdK Berlin - Seedfunding for Creative Collaborations

Photo and film: Markus Zahradnik

Making of photo: Kuba Dabrowski

Photo no 1, 2: Taran Wilkhu

3D print: Tim Schütze

Sound: Mariano Rosales

Sculpture: Marek Elsner

General support : Marcus Naumann, Michal Pecko

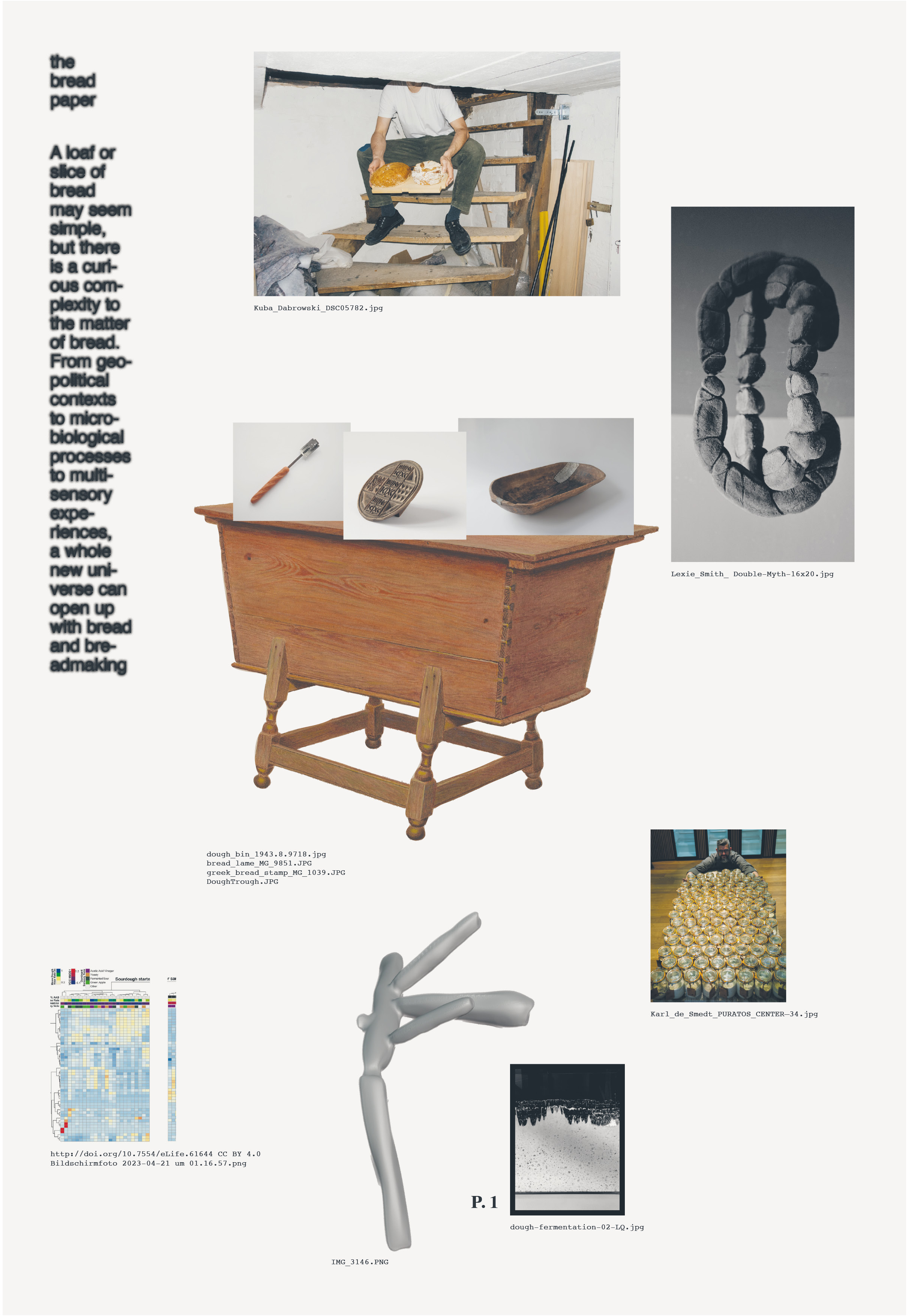

“The Bread-Paper” ( project newspaper)

“The “Bread-Paper” has been initiated as part of the exhibition “BROT: baking the future”. This first issue includes interviews with key players from a broad range of different fields of knowledge, such as microbiology, psychology, agriculture, art, the bread-making industry, and geography. The objective of the “Bread-Paper” is to reveal the complexity of bread and bread-making. However, the “Bread-Paper” by no means lays claim to being complete; instead, it aims to present ongoing explorations of the intricacy of bread worlds.”

Editorial: Maciej Chmara, Dr. Hannah Varga, Anna Rosinke

Graphic design: Ortner etc.

Interviews with: Lisa Kappel, Helmut Gragger, Klara Czerniewska-Andryszczyk, Josef Weghaupt, Karl de Smedt, Friedrich Longin, Regine Schönlechner, Heinrich Grausgruber, Corinne Mynatt, Sang-hyeok Lee, Jessica Barnes, Charles Spence, Lexie Smith, Rob Dunn, Sudeep Agarwala

The Cooking Ape Institute

Neowranghamism - the society of food preparation.

(A fictional Interview, that was developed in the frame of the MUSAE residency. The references to scientists and chefs in this text are used in the context of designing a possible and make no claim to scientific correctness. This text has to be seen as a project in the context of speculative design and not as a paper in the scientific understanding).

Abstract:

In an increasingly digitalized society, the physical and psychological needs of sensory activities are often neglected. In evolutionary terms, the human brain corresponds to the brain of a person from several thousand years ago and is not prepared for the strong visual focus that digitalization brings to our everyday lives. Our senses provide us with orientation and mental balance. However, the way they work cannot be separated from each other; it is always an interplay of several senses that allows us to perceive the world. In psychology, this is known as a multi-sensory experience and is particularly prominent in the culinary world, where haptics, acoustics, olfactory, gustatory and visual senses create a shared experience. Just as the senses were considered separately for a long time, we are still separating the individual areas of nutrition and are unable to create a holistic approach. The modernist image of the body as a machine that needs fuel is only slowly being overcome. We may still be in our infancy when it comes to understanding the complex world of the microbiome and its influence on our physical and mental wellbeing, but at least we are now aware of it. More and more start-ups, insurance companies and politicians in the healthcare sector are taking an interest in the umbrella term “food as medicine” and personalized nutrition. However, thinking one step further and considering nutrition in the wider context of preparation reveals even greater potential. This isn’t just about cooking directly, as cooking primarily really describes the heating of food. It’s about the general cultural technique and aesthetic practice of preparing food.

Looking at the preparation of food in evolutionary terms, we could argue that our fine motor skills and the development of various technologies and the handling of new materials are strongly linked to the preparation of food.

While in the past, preparing meals and cooking was a very arduous activity that led to the need for more and more automation, in today’s Western society, where a large part of the population spends a lot of time in front of screens, working with food can take on a completely different significance in the context of mental equalization.

In addition to the multi-sensory aspects of preparing food, especially when working with sourdough or other fermented products, there is a microbial exchange that can benefit both the product and the person cooking it.

Cooking can take on a whole new role in our society through a holistic approach, with the cornerstones being personalised nutrition, environmentally friendly nutrition (such as the Planetary Health Diet) and mental health through multi-sensory perception during the preparation process. This concept, leading to improved mental and physical health, is by no means the romanticisation of grandma cooking. This goal can be achieved through the latest technological developments in brain wave analysis, AI-driven recipe development and microbiome sequencing.

Maciej Chmara (M.C.):

Dear Prof Coctione,

Ten years ago, you founded the Cooking Ape Institute at KUH University in cooperation with other universities and established the Neo-Wranghamism Society. A society interested in the aesthetic practice and cultural technique of food preparation.

Laying the foundation stone for the interdisciplinary and inter-university institute was a revolution at that time and controversial among experts. However, the doubts were quickly dispelled and there were many imitators. Can you tell us something about the foundation and why the concept was so revolutionary back then?

Prof. Coctione (P.C.): First of all I need to explain the term cooking. We have used the term cooking, although back then it was classically defined in the context of heated, meaning cooked food. Different cultural techniques of food preparation like fermentation or dough making where not included in today’s holistic understanding of the term. So please excuse me, when I mix these terms in the interview, back to your question…

There were indeed many upheavals in those years. To explain the founding of the institute, I will have to expand a little on the status quo of research at the time.

Personalized nutrition was still a marginal phenomenon and genetic sequencing of the gut microbiome was not yet accessible to everyone. Ultra-processed food was not only widespread but also the main source of nutrition in many countries. The first studies on the health risks posed by these foods were slow to emerge.

Glyphosate, which even then was suspected of causing cancer and, as we now know, has a strong negative influence on our intestinal flora, was not only permitted but was also used on a large scale in agriculture. Glyphosate residues were found for example in over 90% of flour samples at the time. There was too little political will and too much lobbying for politicians to intervene.

The average meat consumption in Western societies was around 600% higher than it is today and was of course not at all compatible with the Planetary Health Diet.

The global population was recovering from more than two years of the COVID-19 pandemic with lockdowns, and the socio-psychological consequences of these were not even foreseeable. The climate situation seemed hopeless, and despite global efforts, no decision could be made to phase out fossil fuels. Artificial intelligence was still in its infancy and, like the entire highly inefficient and chaotic digital world, consumed vast amounts of energy.

It was a time to bury our heads in the sand.

Some of these problems have still not been solved today, but at least we have made some progress in terms of social policy and have been able to establish solutions. I don't want to digress too much, but it's important to remember this time.

In society as a whole, many negative developments could be observed especially in the health of young people. Humans developed more and more intolerances, some of which were only imaginary, mostly when it came to wheat, gluten, or lactose. Initially, the imaginary intolerances were ignored in the sense of classical medicine. The term orthorexia, meaning the phobia of unhealthy food, was coined at the time.

As mentioned earlier, we were also only at the beginning when it came to researching the microbiome. The influence of ultra-processed foods and pesticides on our microbiome has also been poorly investigated to date. An interesting indicator of why we might want to do more research in this area was that in richer countries we could see a stunting of the microbiome.

There seemed to be little pieces of the puzzle everywhere that somehow fit together but didn't quite fit yet.

At the same time, the press spoke of the Anxiety Generation among young people, partly due to social anxiety, on which two years of COVID lockdowns certainly had their influence, as well as the shift of social contacts to the digital sphere. The phenomenon of AI friends only worsened this development.

Of course, this all sounds very dystopian now and there were also good things during this time, but I have to clarify where our starting point was.

M.C.: Not exactly optimistic.

P.C.: Unfortunately, things didn't look any better for younger schoolchildren when it came to social stress or the rapidly spreading picky eater syndrome, which wasn't taken seriously at first. The development of fine motor skills also became a major problem. Yes, many children could not hold their pens properly because they spent hours every day with tablets or phones.

An interesting phenomenon of the "Anxiety Generation" was the millions of ASMR videos on YouTube and other social media that were consumed to calm down. ASMR had also found its way into pop music with musicians like Billie Eilish.

Of course, even back then there were already cries that the digital social and working world was bringing these problems with it. But new devices and technologies just seemed too attractive to pass up. We all know that, in the end, political intervention was necessary in the area of technology. I shouldn't digress too much and come to the boil soon.

We had a lot of discussions with our team of food enthusiasts about how we might solve some of these problems and we didn't realize how interconnected everything was.

Identifying problems in the food sector was quickly done. But cooking itself was not taken seriously by many scientists who were interested in food. They were still too attached to the idea that cooking was only a means to an end.

There was no homogeneous development in cooking in society and many contradictory studies. On the one hand, young people, in particular, were increasingly eating out in restaurants, having food delivered or buying other forms of prepared meals, while at the same time, there were also groups that cooked more complicated multi-course meals and focussed on perfecting sourdough-bread baked at home. On the face of it, it seemed a contradiction in terms that everyday normal cooking was absent, but people were meeting up to cook a 13-course menu by some Michelin star chef at home or watching hours of videos on perfect bread dough folding techniques. "Normal" cooking had simply lost its meaning, seemed uninteresting, and was often rationalized away in stressful everyday life due to time constraints. You could say that we were the first generation for whom it was no longer economically worthwhile to cook. If you lived in a city, it was often cheaper to go out to eat than to cook for yourself. The freedom to choose and the responsibility coming with it shouldn’t be underestimated.

M.C.: I don't want to interrupt you, but could you perhaps briefly explain who were the founding members of the team and why, what we take for granted today was so revolutionary?

P.C.: Yes, of course. That will certainly help to clarify things a little. On the one hand, we had Anne Madden here, who was working on yeast research. She had led various projects on the symbiotic existence of yeasts and wasps and also a project with Rob Dunn to investigate the influence of the microbiome of the baker's hands on the dough. As we all know today, this does of course exist, but until then it was more of a myth. At the time, Anne Madden discovered by chance, actually by cross-checking a study, that the microorganisms already contained in the dough also have an influence on our skin’s microbiome and on digestion. The baker's microbiome seemed in our understanding back then, “unnatural" compared to non-baking people.

At that time, the discourse on interspecies symbiosis or social co-existence emerged in the arts. With her research, Madden made an important contribution to the practical and medical understanding of the inter-species debate. Another scientist, Chris Callewaert, was developing microbiome therapies against pathological odor. It made sense to combine their research and the movement of sourdough bio-hacking or sourdough cyborgs was born. At first, this was a somewhat bizarre and esoteric group of people who worked on sourdough together in strange procedures or even bathed in it to model their microbiome - I admit, that I have also visited a couple of meetings. However, further scientific findings have supported this movement and managed to bring it into the mainstream in a modified form and make it what we know it today.

Another member of our team and also one of the financiers of the institute was Naveen Jain, who at the time was better known for his internet and aerospace companies than for Viome. Today, Viome is the global market leader for personalized microbiome analytics but was just a start-up back then, which had its fair share of difficulties. Viome mainly made a profit from food supplements based on the results of its analyses and was more of a niche product for wealthy people. It was the introduction of these products on a large scale and the cooperation with state health insurance companies that changed the profile of this company. They also had a significant influence on the development of medical recipes based on AI.

A small research team from the University of Oxford, which had also just been founded, joined the institute. Prof Charles Spence, founder of gastrophysics and head of the Crossmodal Research Laboratory, played a key role here. Today, as you know, he is celebrated as a pop star for his research in the field of multi-sensory experience. Also on board, alongside some Ph.D. students, was Philip Burnet, a pioneer when it comes to his findings on neurobiology and the microbiome, and of course Katarina Johnson, who put forward the following hypothesis very early on, I hope I am quoting her correctly here:

„Similar to the 'hygiene hypothesis', which posits that an absence of microbes impairs immune system development, we propose that we may have evolved to depend on our microbes for normal brain function, such that a change in our gut microbiome could have effects on behavior.

The plant-based movement became stronger and stronger in an ethical and ecological context. However, it was also associated with a healthy microbiome. Many fine dining chefs started to serve vegan food. Until that point, fine dining was still dominated by animal produce. Daniel Humm, who transformed his world-famous 3 Star Eleven Madison Park into a vegan restaurant, was also a founding member. Very soon more chefs, bakers and fermentation specialists like for example David Zilber joined our initiative.

The BeMoBil Institute with Prof Gramann from the TU Berlin joined in cooperation with the University of Belgrade and the ETF. This was very important because they were able to help us analyze brain waves in the context of movements and prove our hypothesis of how important cooking is for the body and mind. It seems strange, but until then nobody had studied what happens in the brain during the process of food preparation.

Artists, designers, synthetic biologists, agricultural researchers, experimental musicians, and many other scientists attended our meetings.

I would like to mention the Austrian microbiologist Lisa Kappel. She was instrumental in reformulating cookery recipes. If you look at older cookery books, you only ever find ingredients and techniques, possibly chemistry. We aimed to present the microbiological aspects of cooking in the same way without making the recipe too complicated. It took a rethink to give the cooking, the aesthetic practice, and the microbial exchange the same value as the result, the cooked food.

And well, I was there too, with a background in classical physiological medicine, but I've always been fascinated by cooking.

I'm sure I've forgotten to mention plenty of other people and would like to apologize for that, but we were more of a think tank than a closed group.

M.C.: We all know what that led to, but how did the institute become such a huge success so quickly and was able to influence large sections of society in such a short time?

Dr. C.: First of all, I have to say that although the success is great, there is still a long way to go, we still don't understand many things and much of what we do understand has still not been implemented everywhere.

So, there were all these problems, individual pieces of the puzzle that didn't fit together, and the problem that medicine and research, in general, were very specialized. This meant that classical doctors were not very interested in the psyche, psychologists had little knowledge of the body, there were many black sheep among nutritionists with abstruse theories and in the highly specialized research, neurobiologists, for example, did not talk to microbiologists. From today's perspective, this was madness. It was still the legacy of a modernist way of thinking. However, the development of AI in the field of science, such as System Pro, has helped to outline structural or thematic parallels and even bring together people from completely different branches of research.

In a relatively short time, the previously specialized academia has opened up and cooperated in a much more interdisciplinary way in research and teaching.

I would therefore like to summarize our key points here once again. Various physical and mental illnesses have emerged in a large part of society. An uncontrolled, chaotic, and, above all, unreflected digitalization of everything that could somehow be digitalized - many took neoliberalism too seriously. And the battle against climate change seemed to be lost - if we had acted more decisively back then, we would certainly be in a different situation today, but that's another topic. A large part of society developed fears, social phobias, food intolerances, and fascination with ASMR and there was a real hype around cookery shows and doughfluencers - I mean dough specialists on social media. In summary, it sounds a bit absurd, of course, but these were the approaches of our interdisciplinary group.

Research into interspecies symbiosis developed rapidly and we began to understand the connections, perhaps not yet fully, but at least to surmise them.

It became clear that the depletion of our microbiome had a strong influence on physical health and also a previously underestimated influence on mental health. Through regular genetic sequencing of the gut microbiome, diets could be individualized and adapted. Very soon, a niche product became a regular test available to everyone. The umbrella term, Food as Medicine, was on everyone's lips, but it was clear that this was only part of the solution. Just as in the "hygiene hypothesis", the team was convinced that food could not be separated from its preparation. Despite the latest findings, everyone still behaved as if the body was some kind of device that had to be refueled in order to function. The complexity of our existence could not be reflected in this modernist picture. If, depending on how we define cooking (preparation of food), we say that humans or their ancestors have been cooking for 800,000 to 1.9 million years, the process, in the meaning of the cultural technique or aesthetic practice, is just as much a part of human development as the food itself. This is also where our point of view differed from the classic "Cooking Ape" theory and so the concept of Neo-Wranghamism emerged more as a joke during a long team meeting and some bottles of was and really good orange wine.

To summarize in one sentence, Wrangham attributed our brain growth and thus our development of more complex thinking to the easier digestibility of cooked food. Of course, Wrangham's theory is more complex and includes other physiological changes and the formation of social structures, as well as the definition of gender roles. The social role of eating together was also emphasized and was seen as laying the foundations for the development of language. But the link to the act of preparing food was never really closed. I speculate that it is also a late consequence of gender segregation. Even today, we still can't speak of equality and since everyday cooking seemed to be a woman's job for hundreds of thousands of years until recently, it was simply uninteresting, like many other domestic activities for male-dominated sciences. Only professionalized cooking was reserved for men until recently.

Yet it is obvious that the development of tools, architecture, and, of course, later agriculture can be traced back to the way we gathered, hunted, and prepared food.

As far as I've heard, Wrangham doesn't have much use for the term but is not averse to our complementary theory. We really could have come up with a better name, but oh well... Back on topic.

Criticism of digital development has been around for a long time, with the help of recent developments in mobile EEGs, motion tracking, and easier interpretation of results by artificial intelligence, evidence has been provided that our senses are degenerating due to the lack of stimuli. It wasn't just that senses were gone, but their interaction was gone and the digital world, where anything was possible, was suddenly an empty dreary prison cell for a large part of our brain. Consuming ASMR videos, cookery shows, and observing sourdough influencers led to a kind of multi-sensory placebo effect or supplement drug for the brain, which is why it was so popular. However, it was only a bad copy of the real thing and did not have a positive influence on the development of cerebral grey matter and fine motor skills that complex manual skills can have. No other cultural technique can promote this as much as the preparation of food.

Of course, there are also social aspects and many other things that we associate with cooking, but when the institute was founded, this was a milestone that had not previously played a major role in social discourse.

Industry has tried to rationalize cooking further and further away and our research could lead to a rethink.

When it became clear how important the interplay of haptics, olfaction, acoustics, and optics was in cooking, these findings could be linked to the interspecies discourse. Just as it was clear that our microbiome can change through the processing of sourdough, it also does so through contact with other microorganisms. Suddenly the way was paved for understanding cooking in the same way as we do today in all its complexity, as an elementary component of our existence and not just as a means to an end.

M.C.: How was it possible to achieve such a major change in the ten years since the institute was founded?

P.C.: Since the individual team members had their roots at different universities, we were able to introduce an interdisciplinary Master's and Ph.D. program, which was taught in a hybrid form and also led to a strong development in research. Many of the students who came from classical medicine and psychology, for example, then joined forces and opened psychosomatic practices to better research and establish cooking therapies. Since personalized nutrition was already an issue in some countries and some of it was also included in state health insurance schemes, it was obvious to try it with cooking, because there was no risk and, unlike other expensive therapies, it didn't cost much. Many imitators didn't study with us, but they read the publications and set up interdisciplinary practices or various forms of cooking restaurants. Cooking naturally becomes even more interesting when the social aspect is added, and it is usually not possible to cook at home with 20 people.

The movement became fashionable, and as the ecological food transition was also compatible with our goals, there was broad government support. Other attempts to push society towards healthier and more ecological eating behavior had failed in the decades before.

M.C.: That all sounds very simple form today’s perspective, but surely there was also a headwind? Even today, gastronomy is complaining a lot about the trend of home cooking.

P.C.: I don't believe that traditional gastronomy will ever disappear completely, but of course, certain concepts have to adapt. We should look at cooking realistically and in the context of our entire existence. The preparation of food will not become an end in itself.

A major opponent of the movement is the pharmaceutical industry. It's obviously more lucrative to sell pills than to watch people cook, and the food industry wasn't keen at first either, but eventually, they couldn't ignore the scientific findings and with these, the societal pressure against ultra-processed food became too strong to ignore. However, as we know, the rapid development of synthetic biology in the alt-protein market has brought a large part of the industry back into the fold. The chemical giants have of course suffered, but not only because of changes in the food sector. They were trapped in a fossilized logic and most companies were no longer sustainable. Hence, the pesticide sector and agribusiness were not the death knell in my opinion. To be honest, I don't mourn the loss of this sector either. Companies that were open to change still exist today.

We shouldn't forget that even if the percentage is small, there are still voices that want to go back.

M.C.: Cooking today has a strong influence on the field of medicine and also on our everyday lives, social structures, and our working world. It is on par with other therapeutic techniques such as yoga or the fitness center in terms of popularity, and often even surpasses them. People tend to say that we should get more physically active again.

P.C.: Yes, this is true, but as you may know, we are also bringing more and more physical activity into the kitchen and are endeavoring to make drives for mixers, for example, as analog as possible. However, humans are also lazy animals and we still need a lot of convincing to bring the fitness center into the kitchen and liquidate electric drives in this area as much as possible.

M.C.: We've already come to the end of our time, but since you mentioned the kitchen, I hope you can tell us briefly something about this segment.

P.C.: The fact that we have hardly talked about the kitchen so far is almost like the separation of food and its preparation, that we have criticized. I don't know whether it's an anecdote or based on studies. But a friend who was a designer back then and now runs bread baking courses and works for the bakers' guild once told me that 94% of kitchens and kitchen appliances were designed by non-cooking men. Ten years ago at kitchen trade fairs, you could still hear advertising slogans like: „Even my husband can cook in this kitchen“ - no joke. And everything was supposed to be digitalized and automated.

The Vorwerk Thermomix for example became a mass product.

One has to say, that it was a completely different tool than it is today. The users of this appliance became a kind of laborer for simple tasks. People opened the packaging and poured the contents into the machine. The appliance did the rest, then the person washed it. Insanely depressing. We had become slaves to a food processor and that meant „cooking" for many people.

Vorwerk has done a really good job with today's version, in which the appliance encourages us to cook, is linked to the results of our microbiome analysis, and suggests recipes and preparation techniques depending on our mood. It has also been reduced to the core functions of weighing and precise temperature control. The developers have thought again about what people are good at, what they should be good at, and what machines should do. The company was already on the brink of collapse and the pressure was correspondingly high. I'm pleased that there was such a quick rethink.

Some other manufacturers of kitchen appliances, such as Samsung or Anova, have also managed to rethink the smart kitchen segment. Smart kitchens were mostly about automating as much as possible and at some point, it was like disempowering the person doing the cooking. Cooking lost all its appeal.

When AI found its way into the kitchen and was able to combine "mental microbial health" and ecological aspects in recipe selection, it was a great help, as the parameters for how and what we should cook simply became too complex. It also made the kitchen much more energy efficient. This was because the menu planning included when the oven was heated up and you could use it to bake a casserole, a cake, a loaf of bread, and perhaps something for the neighbors. In the same way, food waste could be massively reduced with the help of AI and intelligent recipe selection.

I would like to emphasize here that it is important to differentiate between what people are good at, which techniques are important, and what is perhaps too complicated for us in terms of the complexity and number of parameters where we can use the help of technology.

This way of cooking will become automatic over time and we will have to rely less on new technologies again and perhaps also carry out microbiome analyses less often because we will learn to listen to our body's needs.

This projects was created by Maciej Chmara as a part of his MUSAE S+T+ARTS Fellowship 2024.

The link to the project here: http://musae.starts.eu/musae/2nd-open-call-scenariosl-by-maciej-chmara/

BROT. Audio Guide (DE)

OFIS collection

A new collection dubbed OFIS – an acronym for office for important stuff (name of our Berlin studio) that came to life in times of Covid lockdown. For OFIS, we restricted ourselves to one size of square timber and plank and a very small palette of colours that have been reoccurring in our work over the past years. The geometry of the objects, defined by their proportions and spacial reduction to archetypal shapes, equally mark a return to earlier works of our studio. The OFIS collection is comprised of an office chair, a kneeling stool, a desk, a floor lamp and a chaise-longue.Year: 2020

To order OFIS collection furniture pieces contact us via email

Living a good life with bread

// “On the Search for Deliciousness – Baking Europe”, Professor Charles Spence

// “Making and breaking bread during the pandemic – Baking Europe”, Professor Charles Spence

// “What is bread? – An attempt”, Maciej Chmara

// “I am standing in a grove of trees” Sudeep Agarwala

// “Breadcrumbs – an anthology of Polish lyrical poetry with the motif of bread”, Klara Czerniewska-Andryszczyk

// “Bread-interview with Giulia”, Maciej Chmara

“Living a good life with bread” is a research project developed within the framework of “Oxford x UdK Berlin. Seedfunding for Creative Collaborations”.

Project partners: Prof. Charles Spence (Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford), Maciej Chmara (Institut für Produkt- und Prozessgestaltung, UdK Berlin) Drawings: Ania Rosinke