The Cooking Ape Institute

Neowranghamism - the society of food preparation.

(A fictional Interview, that was developed in the frame of the MUSAE residency. The references to scientists and chefs in this text are used in the context of designing a possible and make no claim to scientific correctness. This text has to be seen as a project in the context of speculative design and not as a paper in the scientific understanding).

Abstract:

In an increasingly digitalized society, the physical and psychological needs of sensory activities are often neglected. In evolutionary terms, the human brain corresponds to the brain of a person from several thousand years ago and is not prepared for the strong visual focus that digitalization brings to our everyday lives. Our senses provide us with orientation and mental balance. However, the way they work cannot be separated from each other; it is always an interplay of several senses that allows us to perceive the world. In psychology, this is known as a multi-sensory experience and is particularly prominent in the culinary world, where haptics, acoustics, olfactory, gustatory and visual senses create a shared experience. Just as the senses were considered separately for a long time, we are still separating the individual areas of nutrition and are unable to create a holistic approach. The modernist image of the body as a machine that needs fuel is only slowly being overcome. We may still be in our infancy when it comes to understanding the complex world of the microbiome and its influence on our physical and mental wellbeing, but at least we are now aware of it. More and more start-ups, insurance companies and politicians in the healthcare sector are taking an interest in the umbrella term “food as medicine” and personalized nutrition. However, thinking one step further and considering nutrition in the wider context of preparation reveals even greater potential. This isn’t just about cooking directly, as cooking primarily really describes the heating of food. It’s about the general cultural technique and aesthetic practice of preparing food.

Looking at the preparation of food in evolutionary terms, we could argue that our fine motor skills and the development of various technologies and the handling of new materials are strongly linked to the preparation of food.

While in the past, preparing meals and cooking was a very arduous activity that led to the need for more and more automation, in today’s Western society, where a large part of the population spends a lot of time in front of screens, working with food can take on a completely different significance in the context of mental equalization.

In addition to the multi-sensory aspects of preparing food, especially when working with sourdough or other fermented products, there is a microbial exchange that can benefit both the product and the person cooking it.

Cooking can take on a whole new role in our society through a holistic approach, with the cornerstones being personalised nutrition, environmentally friendly nutrition (such as the Planetary Health Diet) and mental health through multi-sensory perception during the preparation process. This concept, leading to improved mental and physical health, is by no means the romanticisation of grandma cooking. This goal can be achieved through the latest technological developments in brain wave analysis, AI-driven recipe development and microbiome sequencing.

Maciej Chmara (M.C.):

Dear Prof Coctione,

Ten years ago, you founded the Cooking Ape Institute at KUH University in cooperation with other universities and established the Neo-Wranghamism Society. A society interested in the aesthetic practice and cultural technique of food preparation.

Laying the foundation stone for the interdisciplinary and inter-university institute was a revolution at that time and controversial among experts. However, the doubts were quickly dispelled and there were many imitators. Can you tell us something about the foundation and why the concept was so revolutionary back then?

Prof. Coctione (P.C.): First of all I need to explain the term cooking. We have used the term cooking, although back then it was classically defined in the context of heated, meaning cooked food. Different cultural techniques of food preparation like fermentation or dough making where not included in today’s holistic understanding of the term. So please excuse me, when I mix these terms in the interview, back to your question…

There were indeed many upheavals in those years. To explain the founding of the institute, I will have to expand a little on the status quo of research at the time.

Personalized nutrition was still a marginal phenomenon and genetic sequencing of the gut microbiome was not yet accessible to everyone. Ultra-processed food was not only widespread but also the main source of nutrition in many countries. The first studies on the health risks posed by these foods were slow to emerge.

Glyphosate, which even then was suspected of causing cancer and, as we now know, has a strong negative influence on our intestinal flora, was not only permitted but was also used on a large scale in agriculture. Glyphosate residues were found for example in over 90% of flour samples at the time. There was too little political will and too much lobbying for politicians to intervene.

The average meat consumption in Western societies was around 600% higher than it is today and was of course not at all compatible with the Planetary Health Diet.

The global population was recovering from more than two years of the COVID-19 pandemic with lockdowns, and the socio-psychological consequences of these were not even foreseeable. The climate situation seemed hopeless, and despite global efforts, no decision could be made to phase out fossil fuels. Artificial intelligence was still in its infancy and, like the entire highly inefficient and chaotic digital world, consumed vast amounts of energy.

It was a time to bury our heads in the sand.

Some of these problems have still not been solved today, but at least we have made some progress in terms of social policy and have been able to establish solutions. I don't want to digress too much, but it's important to remember this time.

In society as a whole, many negative developments could be observed especially in the health of young people. Humans developed more and more intolerances, some of which were only imaginary, mostly when it came to wheat, gluten, or lactose. Initially, the imaginary intolerances were ignored in the sense of classical medicine. The term orthorexia, meaning the phobia of unhealthy food, was coined at the time.

As mentioned earlier, we were also only at the beginning when it came to researching the microbiome. The influence of ultra-processed foods and pesticides on our microbiome has also been poorly investigated to date. An interesting indicator of why we might want to do more research in this area was that in richer countries we could see a stunting of the microbiome.

There seemed to be little pieces of the puzzle everywhere that somehow fit together but didn't quite fit yet.

At the same time, the press spoke of the Anxiety Generation among young people, partly due to social anxiety, on which two years of COVID lockdowns certainly had their influence, as well as the shift of social contacts to the digital sphere. The phenomenon of AI friends only worsened this development.

Of course, this all sounds very dystopian now and there were also good things during this time, but I have to clarify where our starting point was.

M.C.: Not exactly optimistic.

P.C.: Unfortunately, things didn't look any better for younger schoolchildren when it came to social stress or the rapidly spreading picky eater syndrome, which wasn't taken seriously at first. The development of fine motor skills also became a major problem. Yes, many children could not hold their pens properly because they spent hours every day with tablets or phones.

An interesting phenomenon of the "Anxiety Generation" was the millions of ASMR videos on YouTube and other social media that were consumed to calm down. ASMR had also found its way into pop music with musicians like Billie Eilish.

Of course, even back then there were already cries that the digital social and working world was bringing these problems with it. But new devices and technologies just seemed too attractive to pass up. We all know that, in the end, political intervention was necessary in the area of technology. I shouldn't digress too much and come to the boil soon.

We had a lot of discussions with our team of food enthusiasts about how we might solve some of these problems and we didn't realize how interconnected everything was.

Identifying problems in the food sector was quickly done. But cooking itself was not taken seriously by many scientists who were interested in food. They were still too attached to the idea that cooking was only a means to an end.

There was no homogeneous development in cooking in society and many contradictory studies. On the one hand, young people, in particular, were increasingly eating out in restaurants, having food delivered or buying other forms of prepared meals, while at the same time, there were also groups that cooked more complicated multi-course meals and focussed on perfecting sourdough-bread baked at home. On the face of it, it seemed a contradiction in terms that everyday normal cooking was absent, but people were meeting up to cook a 13-course menu by some Michelin star chef at home or watching hours of videos on perfect bread dough folding techniques. "Normal" cooking had simply lost its meaning, seemed uninteresting, and was often rationalized away in stressful everyday life due to time constraints. You could say that we were the first generation for whom it was no longer economically worthwhile to cook. If you lived in a city, it was often cheaper to go out to eat than to cook for yourself. The freedom to choose and the responsibility coming with it shouldn’t be underestimated.

M.C.: I don't want to interrupt you, but could you perhaps briefly explain who were the founding members of the team and why, what we take for granted today was so revolutionary?

P.C.: Yes, of course. That will certainly help to clarify things a little. On the one hand, we had Anne Madden here, who was working on yeast research. She had led various projects on the symbiotic existence of yeasts and wasps and also a project with Rob Dunn to investigate the influence of the microbiome of the baker's hands on the dough. As we all know today, this does of course exist, but until then it was more of a myth. At the time, Anne Madden discovered by chance, actually by cross-checking a study, that the microorganisms already contained in the dough also have an influence on our skin’s microbiome and on digestion. The baker's microbiome seemed in our understanding back then, “unnatural" compared to non-baking people.

At that time, the discourse on interspecies symbiosis or social co-existence emerged in the arts. With her research, Madden made an important contribution to the practical and medical understanding of the inter-species debate. Another scientist, Chris Callewaert, was developing microbiome therapies against pathological odor. It made sense to combine their research and the movement of sourdough bio-hacking or sourdough cyborgs was born. At first, this was a somewhat bizarre and esoteric group of people who worked on sourdough together in strange procedures or even bathed in it to model their microbiome - I admit, that I have also visited a couple of meetings. However, further scientific findings have supported this movement and managed to bring it into the mainstream in a modified form and make it what we know it today.

Another member of our team and also one of the financiers of the institute was Naveen Jain, who at the time was better known for his internet and aerospace companies than for Viome. Today, Viome is the global market leader for personalized microbiome analytics but was just a start-up back then, which had its fair share of difficulties. Viome mainly made a profit from food supplements based on the results of its analyses and was more of a niche product for wealthy people. It was the introduction of these products on a large scale and the cooperation with state health insurance companies that changed the profile of this company. They also had a significant influence on the development of medical recipes based on AI.

A small research team from the University of Oxford, which had also just been founded, joined the institute. Prof Charles Spence, founder of gastrophysics and head of the Crossmodal Research Laboratory, played a key role here. Today, as you know, he is celebrated as a pop star for his research in the field of multi-sensory experience. Also on board, alongside some Ph.D. students, was Philip Burnet, a pioneer when it comes to his findings on neurobiology and the microbiome, and of course Katarina Johnson, who put forward the following hypothesis very early on, I hope I am quoting her correctly here:

„Similar to the 'hygiene hypothesis', which posits that an absence of microbes impairs immune system development, we propose that we may have evolved to depend on our microbes for normal brain function, such that a change in our gut microbiome could have effects on behavior.

The plant-based movement became stronger and stronger in an ethical and ecological context. However, it was also associated with a healthy microbiome. Many fine dining chefs started to serve vegan food. Until that point, fine dining was still dominated by animal produce. Daniel Humm, who transformed his world-famous 3 Star Eleven Madison Park into a vegan restaurant, was also a founding member. Very soon more chefs, bakers and fermentation specialists like for example David Zilber joined our initiative.

The BeMoBil Institute with Prof Gramann from the TU Berlin joined in cooperation with the University of Belgrade and the ETF. This was very important because they were able to help us analyze brain waves in the context of movements and prove our hypothesis of how important cooking is for the body and mind. It seems strange, but until then nobody had studied what happens in the brain during the process of food preparation.

Artists, designers, synthetic biologists, agricultural researchers, experimental musicians, and many other scientists attended our meetings.

I would like to mention the Austrian microbiologist Lisa Kappel. She was instrumental in reformulating cookery recipes. If you look at older cookery books, you only ever find ingredients and techniques, possibly chemistry. We aimed to present the microbiological aspects of cooking in the same way without making the recipe too complicated. It took a rethink to give the cooking, the aesthetic practice, and the microbial exchange the same value as the result, the cooked food.

And well, I was there too, with a background in classical physiological medicine, but I've always been fascinated by cooking.

I'm sure I've forgotten to mention plenty of other people and would like to apologize for that, but we were more of a think tank than a closed group.

M.C.: We all know what that led to, but how did the institute become such a huge success so quickly and was able to influence large sections of society in such a short time?

Dr. C.: First of all, I have to say that although the success is great, there is still a long way to go, we still don't understand many things and much of what we do understand has still not been implemented everywhere.

So, there were all these problems, individual pieces of the puzzle that didn't fit together, and the problem that medicine and research, in general, were very specialized. This meant that classical doctors were not very interested in the psyche, psychologists had little knowledge of the body, there were many black sheep among nutritionists with abstruse theories and in the highly specialized research, neurobiologists, for example, did not talk to microbiologists. From today's perspective, this was madness. It was still the legacy of a modernist way of thinking. However, the development of AI in the field of science, such as System Pro, has helped to outline structural or thematic parallels and even bring together people from completely different branches of research.

In a relatively short time, the previously specialized academia has opened up and cooperated in a much more interdisciplinary way in research and teaching.

I would therefore like to summarize our key points here once again. Various physical and mental illnesses have emerged in a large part of society. An uncontrolled, chaotic, and, above all, unreflected digitalization of everything that could somehow be digitalized - many took neoliberalism too seriously. And the battle against climate change seemed to be lost - if we had acted more decisively back then, we would certainly be in a different situation today, but that's another topic. A large part of society developed fears, social phobias, food intolerances, and fascination with ASMR and there was a real hype around cookery shows and doughfluencers - I mean dough specialists on social media. In summary, it sounds a bit absurd, of course, but these were the approaches of our interdisciplinary group.

Research into interspecies symbiosis developed rapidly and we began to understand the connections, perhaps not yet fully, but at least to surmise them.

It became clear that the depletion of our microbiome had a strong influence on physical health and also a previously underestimated influence on mental health. Through regular genetic sequencing of the gut microbiome, diets could be individualized and adapted. Very soon, a niche product became a regular test available to everyone. The umbrella term, Food as Medicine, was on everyone's lips, but it was clear that this was only part of the solution. Just as in the "hygiene hypothesis", the team was convinced that food could not be separated from its preparation. Despite the latest findings, everyone still behaved as if the body was some kind of device that had to be refueled in order to function. The complexity of our existence could not be reflected in this modernist picture. If, depending on how we define cooking (preparation of food), we say that humans or their ancestors have been cooking for 800,000 to 1.9 million years, the process, in the meaning of the cultural technique or aesthetic practice, is just as much a part of human development as the food itself. This is also where our point of view differed from the classic "Cooking Ape" theory and so the concept of Neo-Wranghamism emerged more as a joke during a long team meeting and some bottles of was and really good orange wine.

To summarize in one sentence, Wrangham attributed our brain growth and thus our development of more complex thinking to the easier digestibility of cooked food. Of course, Wrangham's theory is more complex and includes other physiological changes and the formation of social structures, as well as the definition of gender roles. The social role of eating together was also emphasized and was seen as laying the foundations for the development of language. But the link to the act of preparing food was never really closed. I speculate that it is also a late consequence of gender segregation. Even today, we still can't speak of equality and since everyday cooking seemed to be a woman's job for hundreds of thousands of years until recently, it was simply uninteresting, like many other domestic activities for male-dominated sciences. Only professionalized cooking was reserved for men until recently.

Yet it is obvious that the development of tools, architecture, and, of course, later agriculture can be traced back to the way we gathered, hunted, and prepared food.

As far as I've heard, Wrangham doesn't have much use for the term but is not averse to our complementary theory. We really could have come up with a better name, but oh well... Back on topic.

Criticism of digital development has been around for a long time, with the help of recent developments in mobile EEGs, motion tracking, and easier interpretation of results by artificial intelligence, evidence has been provided that our senses are degenerating due to the lack of stimuli. It wasn't just that senses were gone, but their interaction was gone and the digital world, where anything was possible, was suddenly an empty dreary prison cell for a large part of our brain. Consuming ASMR videos, cookery shows, and observing sourdough influencers led to a kind of multi-sensory placebo effect or supplement drug for the brain, which is why it was so popular. However, it was only a bad copy of the real thing and did not have a positive influence on the development of cerebral grey matter and fine motor skills that complex manual skills can have. No other cultural technique can promote this as much as the preparation of food.

Of course, there are also social aspects and many other things that we associate with cooking, but when the institute was founded, this was a milestone that had not previously played a major role in social discourse.

Industry has tried to rationalize cooking further and further away and our research could lead to a rethink.

When it became clear how important the interplay of haptics, olfaction, acoustics, and optics was in cooking, these findings could be linked to the interspecies discourse. Just as it was clear that our microbiome can change through the processing of sourdough, it also does so through contact with other microorganisms. Suddenly the way was paved for understanding cooking in the same way as we do today in all its complexity, as an elementary component of our existence and not just as a means to an end.

M.C.: How was it possible to achieve such a major change in the ten years since the institute was founded?

P.C.: Since the individual team members had their roots at different universities, we were able to introduce an interdisciplinary Master's and Ph.D. program, which was taught in a hybrid form and also led to a strong development in research. Many of the students who came from classical medicine and psychology, for example, then joined forces and opened psychosomatic practices to better research and establish cooking therapies. Since personalized nutrition was already an issue in some countries and some of it was also included in state health insurance schemes, it was obvious to try it with cooking, because there was no risk and, unlike other expensive therapies, it didn't cost much. Many imitators didn't study with us, but they read the publications and set up interdisciplinary practices or various forms of cooking restaurants. Cooking naturally becomes even more interesting when the social aspect is added, and it is usually not possible to cook at home with 20 people.

The movement became fashionable, and as the ecological food transition was also compatible with our goals, there was broad government support. Other attempts to push society towards healthier and more ecological eating behavior had failed in the decades before.

M.C.: That all sounds very simple form today’s perspective, but surely there was also a headwind? Even today, gastronomy is complaining a lot about the trend of home cooking.

P.C.: I don't believe that traditional gastronomy will ever disappear completely, but of course, certain concepts have to adapt. We should look at cooking realistically and in the context of our entire existence. The preparation of food will not become an end in itself.

A major opponent of the movement is the pharmaceutical industry. It's obviously more lucrative to sell pills than to watch people cook, and the food industry wasn't keen at first either, but eventually, they couldn't ignore the scientific findings and with these, the societal pressure against ultra-processed food became too strong to ignore. However, as we know, the rapid development of synthetic biology in the alt-protein market has brought a large part of the industry back into the fold. The chemical giants have of course suffered, but not only because of changes in the food sector. They were trapped in a fossilized logic and most companies were no longer sustainable. Hence, the pesticide sector and agribusiness were not the death knell in my opinion. To be honest, I don't mourn the loss of this sector either. Companies that were open to change still exist today.

We shouldn't forget that even if the percentage is small, there are still voices that want to go back.

M.C.: Cooking today has a strong influence on the field of medicine and also on our everyday lives, social structures, and our working world. It is on par with other therapeutic techniques such as yoga or the fitness center in terms of popularity, and often even surpasses them. People tend to say that we should get more physically active again.

P.C.: Yes, this is true, but as you may know, we are also bringing more and more physical activity into the kitchen and are endeavoring to make drives for mixers, for example, as analog as possible. However, humans are also lazy animals and we still need a lot of convincing to bring the fitness center into the kitchen and liquidate electric drives in this area as much as possible.

M.C.: We've already come to the end of our time, but since you mentioned the kitchen, I hope you can tell us briefly something about this segment.

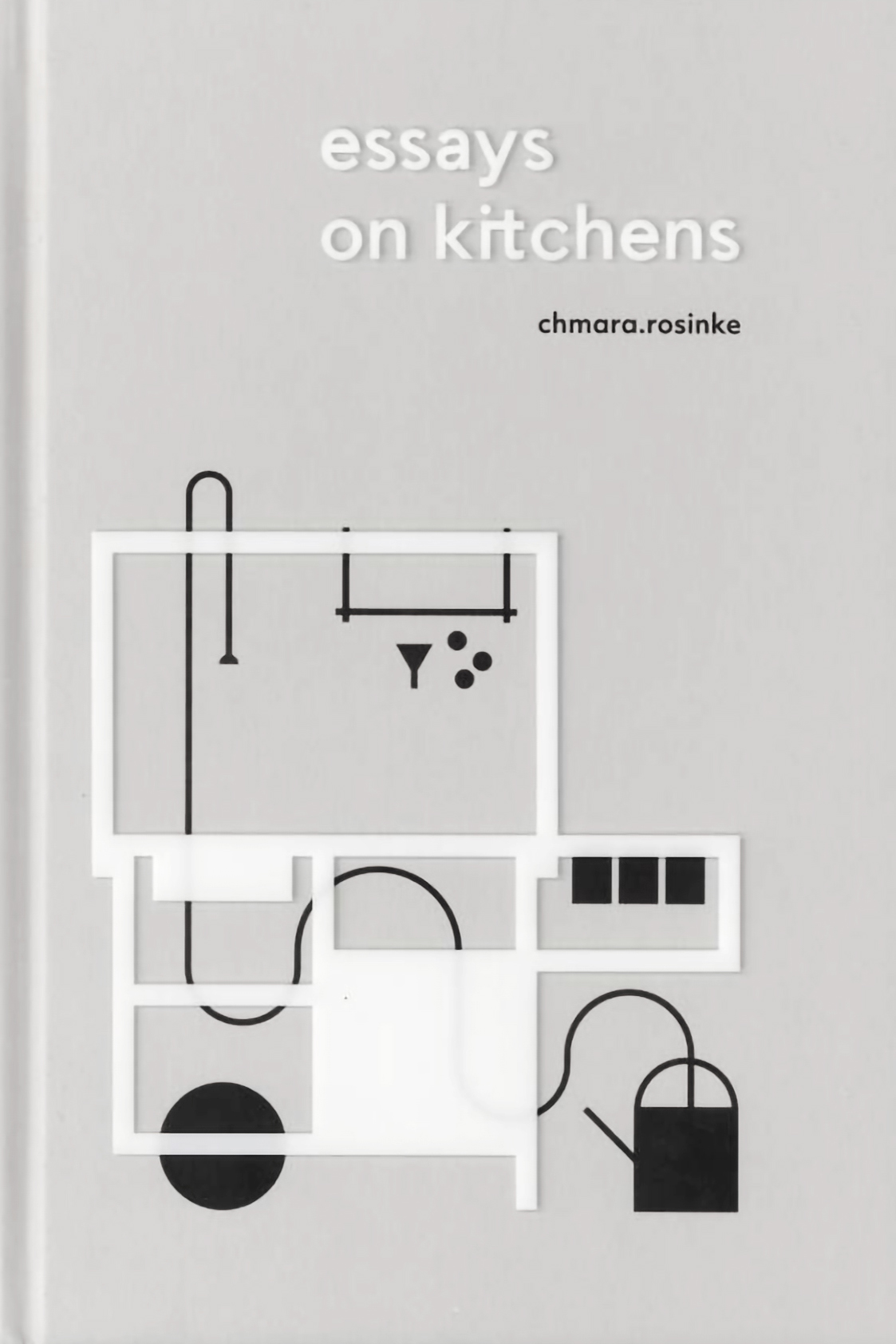

P.C.: The fact that we have hardly talked about the kitchen so far is almost like the separation of food and its preparation, that we have criticized. I don't know whether it's an anecdote or based on studies. But a friend who was a designer back then and now runs bread baking courses and works for the bakers' guild once told me that 94% of kitchens and kitchen appliances were designed by non-cooking men. Ten years ago at kitchen trade fairs, you could still hear advertising slogans like: „Even my husband can cook in this kitchen“ - no joke. And everything was supposed to be digitalized and automated.

The Vorwerk Thermomix for example became a mass product.

One has to say, that it was a completely different tool than it is today. The users of this appliance became a kind of laborer for simple tasks. People opened the packaging and poured the contents into the machine. The appliance did the rest, then the person washed it. Insanely depressing. We had become slaves to a food processor and that meant „cooking" for many people.

Vorwerk has done a really good job with today's version, in which the appliance encourages us to cook, is linked to the results of our microbiome analysis, and suggests recipes and preparation techniques depending on our mood. It has also been reduced to the core functions of weighing and precise temperature control. The developers have thought again about what people are good at, what they should be good at, and what machines should do. The company was already on the brink of collapse and the pressure was correspondingly high. I'm pleased that there was such a quick rethink.

Some other manufacturers of kitchen appliances, such as Samsung or Anova, have also managed to rethink the smart kitchen segment. Smart kitchens were mostly about automating as much as possible and at some point, it was like disempowering the person doing the cooking. Cooking lost all its appeal.

When AI found its way into the kitchen and was able to combine "mental microbial health" and ecological aspects in recipe selection, it was a great help, as the parameters for how and what we should cook simply became too complex. It also made the kitchen much more energy efficient. This was because the menu planning included when the oven was heated up and you could use it to bake a casserole, a cake, a loaf of bread, and perhaps something for the neighbors. In the same way, food waste could be massively reduced with the help of AI and intelligent recipe selection.

I would like to emphasize here that it is important to differentiate between what people are good at, which techniques are important, and what is perhaps too complicated for us in terms of the complexity and number of parameters where we can use the help of technology.

This way of cooking will become automatic over time and we will have to rely less on new technologies again and perhaps also carry out microbiome analyses less often because we will learn to listen to our body's needs.

This projects was created by Maciej Chmara as a part of his MUSAE S+T+ARTS Fellowship 2024.

The link to the project here: http://musae.starts.eu/musae/2nd-open-call-scenariosl-by-maciej-chmara/